The Legal 500 UK Awards 2018 recognises and rewards the very best of the best across the legal industry. We pride ourselves on the thorough, in-depth research we carry out in order to produce our rankings of firms and sets in the UK. This leaves us in a unique position to be able to identify the teams which warrant particular recognition. Continue reading “The Legal 500 UK Awards 2018”

Striking out

A 23-year-old became the most sought-after baseball player last year when he announced he would leave Japan to play in the US. Shohei Ohtani was already a phenomenon. Able to pitch and hit – a skillset as rare as hens’ teeth in the game and infinitely more prized – league rules limiting his initial pay guaranteed whichever team landed him an absolute bargain.

The enforcers

No-one could accuse the UK competition regulators of lacking scope and vigour. The main regulator, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has rightly gained a reputation for robust enforcement. The nomination of former Conservative MP Andrew Tyrie as the CMA’s new chair is expected to reinforce its standing as a no-nonsense agency. But as it faces up to Brexit, it will have to shoulder a far heavier burden.

Welcome to the hurricane

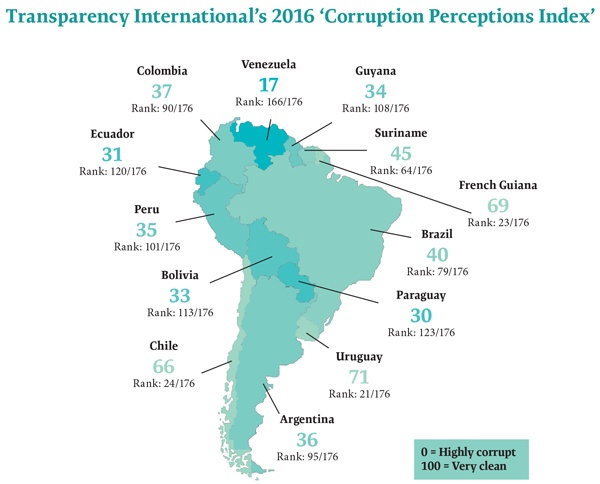

It has been a turbulent few years for many of those in the upper echelons of Brazilian politics and business. Around the world, headlines have been filled with sleazy tales of corruption, perhaps most notably the bribery and kickback scandal emanating from state-backed oil giant Petrobras, embroiling many high-profile individuals and entities across the region.

Trust me, I’m a lawyer…

Academic and Thinkers50 honouree Rachel Botsman is focused on trust. Of late, that focus has looked at how technology has shifted our understanding of trust and impacted on both our personal and professional lives.

Financing corporate legal costs: self-finance vs outside backing

In the course of Burford Capital’s nearly nine years in business and in talking to hundreds of lawyers about financing fees and disbursements associated with commercial litigation and arbitration, it has been our experience that quantifying and comparing the relative costs and benefits of financing models is the most effective way to talk to clients about legal finance. Once clients appreciate that external financing addresses several of the perpetual pain points associated with litigation – such as its negative accounting impact and its potential influence on share price – the decision to use legal finance seems simple. Clients who use litigation finance are united less by their need for cash to pay for legal costs than they are by their understanding of the comparative benefits of paying out-of-pocket versus working with a finance partner.

Continue reading “Financing corporate legal costs: self-finance vs outside backing”

Regulators Struggle to Raise the Standard of Care for Financial Advice

On March 15, 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (“Fifth Circuit”) in a 2-1 decision vacated the Obama-era U.S. Department of Labor’s (“DOL”) Fiduciary Rule (“Fiduciary Rule”), which responded to a historical shift from traditional pension plans to individually managed accounts, such as individual retirement accounts (“IRAs”) and 401(k)s. The Fiduciary Rule would have applied a fiduciary standard to advisors who provide investment advice in the distribution phase of individual retirement plan assets or rollovers, thus imposing trust law standards of care and undivided loyalty. The DOL—now under the Trump administration—did not ask the Fifth Circuit to review its decision and has until June 13 to request the U.S. Supreme Court to hear its appeal.

At the same time, a best interest standard of conduct for advisors remains under active consideration by the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and New York Department of Financial Services (“NYDFS”). Although in apparent agreement that individual investors deserve additional protection, it remains to be seen whether these regulators can develop a harmonized standard of care. At a public hearing on April 18, the SEC Commissioners voted 4-1 to propose rulemaking and interpretations imposing a best interest standard on broker-dealers and clarifying the standard of conduct for investment advisors. In December 2017, the NYDFS proposed a best interest standard for the sale of life insurance and annuity products in an amendment to its suitability regulation. On April 27, in response to industry comments, the NYDFS updated its proposal, which will go into effect following a 30-day notice and comment period.

Last year, in response to the DOL’s Fiduciary Rule, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (“NAIC”) also proposed a best interest standard for the sale of annuity products to be added to its Suitability in Annuity Transactions Model Regulation. Following the Fifth Circuit’s decision, the NAIC announced it is reconsidering a best interest standard and will focus on strengthening the current suitability standard. In fact, Vice Chairman of the Annuity Suitability Working Group, Iowa Insurance Commissioner Doug Ommen recently said that the current suitability model regulation is protecting investors. He went on to state, “I’m very uncomfortable with the idea that we’re going to push aside what is now a history and tradition of suitability, create something new and then wait for a number of years of SEC deliberation on what that means.”

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR FIDUCIARY RULE

As the dissent in the Fifth Circuit noted: “Over the last forty years, the retirement-investment market has experienced a dramatic shift toward individually controlled retirement plans and accounts. Whereas retirement assets were previously held primarily in pension plans controlled by large employers and professional money managers, today, IRAs and participant-directed plans, such as 401(k)s, have supplemented pensions as the retirement vehicles of choice, resulting in individual investors having greater responsibility for their own retirement savings. This sea change within the retirement-investment market also created monetary incentives for investment advisors to offer conflicted advice, a potentiality the controlling regulatory framework was not enacted to address.”

Despite this “sea change,” the majority opinion struck down the Fiduciary Rule. Conducting a Chevron analysis, the majority determined that Congress had clearly defined the scope of an investment advice fiduciary to be limited to employer – or union – sponsored retirement and welfare benefit plans. As a result, it held that the DOL lacked the statutory authority to revise the term to include IRAs and participant-directed plans during the distribution phase.

The majority’s decision aligned with the position of financial service providers and insurance companies, which strengthened their challenge of the Fiduciary Rule by claiming it could deprive individual investors of professional investment advice. According to the plaintiffs, the cost of compliance with additional regulations would force investment professionals to raise their fees or stop offering services. Indeed, the majority noted that Metlife, AIG and Merrill Lynch had already reduced their presence in the brokerage and retirement-investment market. Despite the complexity of the Fiduciary Rule and the changes in conduct it requires, it is fair to ask whether these companies cannot in fact absorb these additional costs. From the consumer’s point of view, it seems incongruous that an employee could build up substantial retirement savings in the accumulation phase of a 401(k) plan with fiduciary protections only to be faced with a conflicted investment professional during the distribution phase or that an individual with an IRA never had the protection of non-conflicted advice.

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Notwithstanding the Fifth Circuit’s decision, increased regulation of financial service providers and insurance producers may impose a best interest standard of care. As we noted, the SEC Commissioners voted 4-1 to propose a best interest standard for broker-dealers and interpretations designed to “enhance the quality and transparency of investors’ relationships with investment advisors and broker-dealers while preserving access to a variety of advice relationships and investment products.” Commissioner Kara Stein, who cast the dissenting vote, stated, however, that the proposals essentially preserved the existing suitability standard. Even the Commissioners who voted in favor of the proposals made it clear that they were relying on the industry to help shape the final rule. According to a press release from the SEC, the proposals:

- Require broker-dealers to act in the best interest of their retail customers when making a recommendation, without putting their own interest ahead of their customers;

- Reaffirm and clarify the standard of conduct investment advisors owe to their customers; and

- Mandate broker-dealers and investment advisors provide retail customers with a relationship summary on a standardized form to disclose the services they offer, the standard of conduct by which they are bound, the fees they charge and potential conflicts of interest.

Jay Clayton has stated his goal is for a best interest standard that would ultimately harmonize regulation for the industry. The NAIC also hopes to build consensus, especially with the SEC. Regulatory harmonization would appease financial service providers and insurance companies burdened by overlapping regulators and regulations. This regulatory overlap in part arises from the SEC regulating variable annuities and registered fixed-indexed annuities. At the same time, state insurance commissioners supervise unregistered annuities and life insurance products.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF INSURANCE COMMISSIONERS

Both the NAIC and NYDFS have considered raising the standard of conduct for how investment professionals market insurance products. In November 2017, the NAIC proposed the Suitability and Best Interest Standard of Conduct in Annuity Transactions Model Regulation, which would require that investment professionals ensure an annuity is not only suitable for the investor—as the rule currently requires—but also that the annuity is in the investor’s best interest. Under the proposed rule, “best interest” is defined as, “at the time the annuity is issued, acting with reasonable diligence, care, skill, and prudence in a manner that puts the interest of the consumer first and foremost.” The proposed model rule would also require investment professionals to make certain disclosures to their clients, including whether they have any material conflicts of interest. However, the NAIC appears to have retreated from this proposal. In response to the Fifth Circuit’s decision, the NAIC’s Annuity Suitability Working Group Chairman, Idaho Insurance Commissioner Dean Cameron, called for a round of comments to strengthen the current suitability model rule, which 39 jurisdictions have already adopted. This decision to restart the process was reportedly welcomed by many state insurance regulators.

NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF FINANCIAL SERVICES

Typically, the NAIC approves model rules which state regulators adopt. As is often the case, however, the NYDFS proposed its own rule. In December 2017, the NYDFS introduced a best interest standard in an amendment to Insurance Regulation 187, entitled Suitability in Life Insurance and Annuity Transactions. In April, following a 60-day comment period, the NYDFS issued an updated regulation. The NYDFS would raise the current suitability standard to a best interest standard. Their definition differs from that of the NAIC’s proposed best interest standard in several important ways. The NYDFS clearly states that investment professionals must make recommendations without regard to their own interests, while the NAIC appears to allow investment professionals to consider their own interests as long as they prioritize those of their client. More significantly, the NYDFS applies the best interest standard to sales of both annuities and life insurance as well as policy modifications, replacements, and recommendations to investors, even when they do not enter into a transaction.

As it was with cybersecurity regulations, the NYDFS is positioned to be a first-mover standard-setter. In the initial press release announcing the proposed rule, Governor Andrew Cuomo emphasized that New York embraces its role as a defender of consumer rights. Moreover, in a recent interview, NYDFS Superintendent Maria Vullo stated that the NYDFS hopes the best interest standard becomes “a national standard for life and annuity products.”

STATE LEGISLATION AND PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

Although the NYDFS has spearheaded the effort to raise the standard of conduct for the insurance industry, state legislatures have also enacted laws or introduced bills that offer individual investors protection. In January, New Jersey lawmakers reintroduced legislation that would require investment professionals to disclose to their clients if they are not bound by a fiduciary standard. In June 2017, Connecticut Governor Dannell Malloy passed an act that requires investment professionals managing non-ERISA plans to disclose to their clients any conflicts of interest. No state has gone further than Nevada, which in June 2017 required broker-dealers and investment advisors to act as fiduciaries for their clients.

It is uncertain whether the Fifth Circuit’s decision will preempt the Nevada law or otherwise discourage states from moving forward with pro-consumer legislation. Maryland lawmakers have already scaled back a bill that would have imposed a fiduciary duty on broker-dealers, insurance agents, and investment advisors. However, Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth William Galvin stated that in the absence of federal legislation, states bear a responsibility to protect consumers. In February, Secretary Galvin charged Scottrade Inc. with violation of both the Fiduciary Rule and the company’s internal policies, alleging that Scottrade Inc. arranged contests among brokers in order to boost sales of retirement products.

Professional organizations have also proposed a best interest standard of care. In June 2015, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association proposed a rule that would establish a best interest standard for broker-dealers serving individual clients, and advocated for the SEC to do the same. In March, the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc. unanimously approved a rule that requires Certified Financial Planners to act in the best interests of their clients at all times when providing financial advice.

OUTLOOK

Regardless of which regulations or regulators prevail, the transition to a new standard of conduct will not be seamless. The implementation of the Fiduciary Rule had already resulted in multiple claims brought against brokerages. As previously noted, Massachusetts brought a claim against Scottrade Inc. for an alleged violation of the Fiduciary Rule. In April, plaintiffs in a class action suit alleged that Edward Jones moved clients from commission-based to fee-based accounts, even when it was not in their best interests. The plaintiffs claim that Edward Jones engaged in reverse churning, using the Fiduciary Rule to justify a change in compensation method.

The decision to strike down the Fiduciary Rule may only create additional challenges, as investment professionals must weigh modifying their practice to reflect the regulatory landscape pre-Fiduciary Rule against waiting for further action by federal or state regulators, such as adoption by the SEC of some form of its proposed best interest regulation. The NAIC is reconsidering its suitability model regulation in the wake of the Fifth Circuit’s decision and the SEC’s most recent proposals. The NYDFS remains steadfast in its decision to move forward with its own best interest rule for life and annuity sales.

Restrictive Covenants under Turkish Law

INTRODUCTION

The success of a business resides in its employees. Even the biggest corporate structures depend on its employees to conduct its business. That is why, during the course of employment employer’s valuable information that is integral to its activities such as its business models, client profiles and marketing strategies are exposed to the use of its employees and once such become known by the employees they cannot be unknown. Therefore, the employers become vulnerable to misuse of such insight by the ex-employees after the termination of the employment relationship. While in most of the legal systems, the employee is under the duty of confidentiality and non-compete during the term of the employment, these issues may be at stake following the cease of employment. Hence, there is a growing trend in the business world to provide some level of legal protection to the employer against its ex-employees. The instruments to achieve such protection are called the “restrictive covenants” with which the employer restricts certain behavior of its former employees for a period following the termination.

There are different types of restrictive covenants common in employment contracts of the senior or high skilled employees with access to sensitive information of the employer designed for preventing the employee from entering into direct competition against the employer (non-compete); preventing him/her from accepting business from clients and/or contracting the clients with/without them approaching to the employee first (non-dealing); and preventing an employee from soliciting other employees to join him/her in the supposedly new business (non-solicitation). While such requirements are beneficial for the protection of business, they are in fact restrictions on the employee’s freedom to work, thus legal systems have evolved to adjust such encroaching interests.

The abovementioned needs of the employees have also played its part in Turkey. Including such provisions in employment contracts are becoming more and more popular. From a legal point of view, non-compete, non-solicitation and confidentiality obligations are the types of restrictive covenants recognised under Turkish law. While only non-compete covenant is regulated in detail under the Turkish Code of Obligations (“TCO”), the High Court accepts that non-solicitation and confidentiality covenants shall also be interpreted within the scope of the regulations on non-compete covenants. Other clauses of non-employment and non-dealing are not defined under Turkish law and are not commonly used in Turkey. Still, as long as the limitations set forth under the Turkish Code of Obligations are fulfilled, the covenants shall be enforceable due to the principle of freedom of contract.

In light of the abovementioned, our examination will be limited to non-compete obligations of an employee within the context of Turkish Employment Law.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE CONTRACT

Under Turkish law, the employee is under a duty of loyalty, which includes a prohibition on competing with his/her employers, for the term of the employment as per Article 396 of TCO. Moreover, Article 25(II)(e) of Turkish Code of Labour designates behaviours in breach of such duty as a ground for termination of the employment contract with justified reasons and immediate effect. However, once the employment contract is terminated, such duty dissolves. That is why, for an employer to best protect its business interests post-employment, (s)he should impose a specific non-compete obligation on the employees. The usual way to draft such an obligation is to include a non-compete provision in the employment contract. However, if preferred, a separate agreement setting forth such duties may also be drafted. In any case, the agreement shall be in writing.

ENFORCEABILITY AND ESSENTIAL TERMS

In line with the universal principles, Turkish law also aims to balance the opposing interests of the employee and the employer while allowing the employer to impose a restriction over the employee’s freedom of work. That is why, Articles 444 and 445 of the TCO set forth some mandatory limitations as to the scope of restriction so that it shall not be far-reaching than what is suitable for preserving the justified business interests of the employer. According to such provisions:

- The employer must have legitimate business interests to request such a restriction,

- Restrictive covenants should not include unfair restrictions on location, time and type of activities which put the economic future of the employee in jeopardy,

- Except under special circumstances, time restriction should not be longer than two years.

In essence, restrictive covenants should go no further than is necessary to protect the legitimate business interests of the employer and at the same time should not unreasonably jeopardise the economic future of the employee. Therefore, a narrower scope would increase the possibility of enforcement. If the scope of the restrictive covenant is too broad, the employer would need to prove that such restrictions are reasonable and justifiable. While a judge can limit the scope of the covenant if, considering all relevant conditions, (s)he deems such as excessive, (s)he may also declare the covenant null and void if the employer does not have a legitimate business interest at stake.

LEGITIMATE BUSINESS INTERESTS OF THE EMPLOYER

Legitimate business interests of the employer may be summarised as the employee’s access to information on the production, business secrets and client portfolio of the employer, and the effect on the employer’s profits of the use of such information.

For a restrictive covenant to be valid, the employee must have access to information related to business and production, which must qualify as confidential information and a business secret, and the employee must be able to use the information for the employee’s economic benefits. Whether particular production technologies, processes, inventions, software and hardware, financial records, business plans and strategies are business secrets will be examined by the court on a case by case basis. On the other hand, if the employee gains customers because of the employee’s skills and knowledge (as might be the case for lawyers and doctors), restrictive covenants will be void.

LIMITATIONS AS TO LOCATION

Restrictive covenants must be geographically limited to the areas where the employer is actually conducting business activities and it must not exceed the boundaries of the employer’s actual sphere of activity.

The relevant geographical area may be a city, a region or any place where the employer is conducting business. According to the precedents of the High Court, defining the geographical scope as “Turkey” is too broad.

LIMITATIONS AS TO TERM

Restrictive covenants must be limited to a specific period of time in order to be enforceable against the employee and in any case, TCO does not allow the non-compete obligations, unless there are special circumstances, to exceed two years following the termination of the contract. Moreover, even if the duration is designated for less than two years, the judge may always amend the duration of the restriction if it would jeopardise the economic future of the employee.

LIMITATION AS TO TYPE OF ACTIVITIES

Restrictive covenants should not unreasonably put the economic future of the employee in jeopardy. Therefore, except for in special circumstances, restricted activities should be directly related to the employee’s job and should be limited to the job’s subject matter.

As a general comment, please be noted that the employer is under no duty to provide consideration to the employee in return for covenants under Turkish law. However, in evaluating the reasonableness of the non-compete obligation, thus its enforceability, a judge may consider whether the employee has received any compensation in return for it.

TRANSFER OF BUSINESS

Moreover, under Turkish law, restrictive covenants are not regarded as personal obligations, but rather as having an economic value to the business of the employer. Therefore, upon acquisition of the business, even without a separate agreement, the restrictive covenants shall continue to be applicable. Thus, the acquirer shall be entitled to be protected in the same manner as the new employer, as long as it continues to be active in the same field of business following the transaction.

TERMINATION AND EXPIRY OF THE CONTRACT

According to Article 447 of TCO, an employer terminates the employment contract without any justified cause, or if the employee terminates the employment contract due to a cause attributable to the employer, the non-compete obligation applying to the employee shall also be terminated.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, as in many other jurisdictions, Turkish law also recognizes the employer’s right to impose restrictive covenants for its employees regarding their post-termination period as long as the employer has legitimate business interests at stake because of the business intelligence the employee has gained in relation to the employer’s business. While such covenants are deemed integral to the employee’s duty of loyalty during the course of the employment, it shall be explicitly agreed for the term following the cease of employment. In doing that there are certain limitations (as to form, term, geographic scope and field of activity) to be included in the covenant.

The Hot Topic in United States M&A – Corwin

Introduction

The general question of corporate governance can be summarized, in the context of public companies, as three interrelated questions: who has decision-making authority; how are they constrained in the exercise of that authority; and how are they held accountable for that exercise? In this model, the U.S. approach to corporate governance has historically been very director-centric. In a U.S. public company, the board of directors has substantially more power than in any other major developed legal regime and is subject to fewer formal constraints on the exercise of that power. Not surprisingly, the U.S. approach to corporate governance has developed differently with respect to the means by which boards of directors are held accountable for their decisions. The U.S. market remains the most active with respect to the three leading structural mechanisms for holding boards of directors accountable: hostile takeovers, shareholder activism/proxy fights and, last but not least, direct shareholder litigation against boards of directors.

While the foregoing is true generally with respect to corporate governance, it is particularly true with respect to M&A. Almost all developed legal regimes recognize that “M&A is different” and apply distinct rules of corporate governance to the behavior of boards of directors of target companies in the context of M&A. The most well known model is the U.K. Takeover Code, from which the European Takeover Directive was heavily drawn and which also significantly influenced the takeover codes in other Commonwealth countries. A central premise of the U.K. Takeover Code is “passivity”: it takes power away from the board of directors of a target company.

In the U.S., while the challenge created by corporate governance in the M&A environment has been recognized, the model of director-centric corporate governance has not been abandoned. Instead, the preexisting structures for holding boards of directors accountable are applied with greater force, in particular, judicial supervision of the conduct of boards of directors exercised through private litigation. As is well known and documented, the U.S. is home to substantially more M&A-related shareholder litigation that calls into question the behavior of the boards of directors of U.S. companies. In the context of M&A litigation, the Delaware courts have traditionally been reluctant to give effect to any principle of “stockholder ratification”. This has been based in part on a theoretical model, in which the Delaware courts have noted that directors have their own duties and that the mere fact a majority of the stockholders support a particular transaction does not speak to whether the directors have discharged their duties in proposing that transaction. In addition, the Delaware courts have been concerned by a conceptual problem with the principle of stockholder ratification, as applied in the M&A context. A stockholder vote on a proposed M&A transaction is a binary choice between the transaction, as negotiated by the board of directors, and no transaction at all. It is seldom the case that the stockholders have the ability to send the board of directors back to “try again”; accordingly, a vote by the stockholders to approve a particular transaction cannot as a substantive matter be viewed as the equivalent of stockholder agreement with the proposition that the transaction before them was properly negotiated by a careful and loyal board of directors.

From time to time, the Delaware courts have shown deference to the will of the stockholders. For example, outside the area of conflicted transactions, there is no known example of a Delaware court permanently enjoining a proposed M&A transaction as a result of alleged misbehavior by the board of directors of the target corporation other than in the context of a competing bid for the target company. However, over the last several years there have been three different series of decisions in the Delaware courts that, taken as a whole, seem to reflect a more significant judicial shift in approach to the U.S. director-centric model.

MFW

The first line of cases relates to a transaction in which a majority stockholder buys out the minority stockholders (a “squeeze out”). As a result of judicial concern regarding fair treatment of stockholders in squeeze out transactions, in the 1980s and early 1990s the Delaware courts developed the “entire fairness” standard of judicial review, under which, in a squeeze out, the controlling stockholder and the board of directors of the target company were subject to strict judicial scrutiny focused on whether the squeeze out involved a “fair process” and offered minority stockholders a “fair price”.

As a result of the entire fairness doctrine, squeeze out transactions in Delaware are particularly subject to litigation risk. Almost from its inception, controlling stockholders and their advisors sought to avoid the application of that doctrine through structuring techniques. This led to a series of decisions in the 2000s in which the Delaware courts commented on various alternative structures and evidenced increasing concern that substantive protections for minority stockholders should not depend on the legal structure used for a squeeze out. This process came to a head, and possibly to a conclusion, with the MFW litigation. In MFW, the Delaware courts held that a squeeze out, without regard to structure, would not be subject to the entire fairness standard of review, but would be subject to the more deferential business judgment rule standard of review, if, among other matters, the transaction was negotiated on behalf of the target company by a properly functioning special committee consisting of independent directors and was approved by a fully informed, uncoerced vote of minority shareholders representing a majority of the shares not held by the controlling stockholder (the so-called “majority of the minority vote”). MFW has now become the prevailing model for squeeze out transactions in Delaware.

It is worth noting at the outset that MFW is not a decision based on stockholder ratification. It is, instead, a decision about judicial standard of review. However, as a practical matter, the determination of the standard of review comes very close to compelling the conclusion on the merits: controlling stockholders routinely failed review under the entire fairness doctrine and routinely survived judicial review under the business judgment standard.

As noted earlier, the entire fairness doctrine had two components—fair process and fair price. One can see that the MFW standard itself meets the requirement of fair process, with the properly functioning special committee of independent directors and the majority of the minority vote together being a fair process. So what happened to the concern about fair price that originally led the Delaware courts to include that as a component as of the entire fairness doctrine? One could say that the Delaware courts simply decided not to worry about fair price. On the other hand, it might be the courts decided that approval by a majority of the minority vote should be regarded judicially as compelling evidence of fair price. If MFW were the only line of cases involved here, it would be hard to know what was motivating the Delaware courts. But MFW is not alone.

Deal Price in Appraisal Litigation

Under the Delaware corporation law, stockholders who vote against a merger are entitled to seek appraisal, i.e., to decline to receive the agreed merger consideration and instead to receive cash at a valuation of the target company determined by the Delaware Court of Chancery in an adversarial valuation proceeding known as an appraisal. The right to appraisal has been a feature of the Delaware corporation law for many decades, albeit rarely seen. Starting in the middle of the last decade, however, and accelerating through much of the current decade, there was a significant increase in the volume of appraisal demands, leading to a significant increase in the number of reported Delaware decisions on the appraisal statute, including the proper way of valuing Delaware target companies for purposes of appraisal.

The most recent Delaware decisions with respect to the proper valuation of a target company in appraisal proceedings have attached extraordinary weight to the agreed deal price itself. As one recent commentator put it, in the absence of some evidence of a conflicted transaction or self-dealing, at the moment in Delaware it is almost impossible to have an appraisal action reach a valuation of the target company greater than an agreed cash price.

As a matter of principle, there is much to like about the Delaware courts’ focus on a deal price. If the purpose of an appraisal proceeding is to determine the fair value of the target company, what better evidence of value is there than an agreed transaction price negotiated at arm’s length? From the perspective of the appraisal statute, however, heavy reliance on the deal price seems illogical. The purpose of the appraisal statute is to give a dissenting stockholder the right to argue for something other than, and presumably greater than, the deal price in the transaction against which the stockholder voted. It would be an overstatement to claim that an overwhelming presumption that the deal price equals appraised fair value eviscerates the appraisal statute, but it is certainly true that it substantially reduces the benefit of the appraisal statute to dissenting stockholders.

Why, after decades of jurisprudence relating to the proper methods for valuing companies in appraisal proceedings, did the Delaware courts adopt a rule attaching so much weight to the agreed deal price? One explanation that has been offered was a judicial attempt to crack down on abusive and expensive appraisal proceedings. Another explanation though, seems more consistent with MFW. Just as, in MFW, one can see the Delaware courts concluding that the fair price component of the entire fairness doctrine should be deemed to be met as a result of uncoerced stockholder approval of the transaction, one can see in the appraisal proceedings the Delaware courts deferring to the judgment of the stockholders (in the form of stockholder approval of an agreed transaction) as compelling evidence of fair value of the target company. But even MFW and the appraisal cases are not alone.

Corwin

The 2015 decision of the Delaware Supreme Court in Corwin is probably the most significant Delaware M&A decision in 15 years. While MFW and the appraisal cases referred to above can be seen as elaborations on existing doctrine, it is hard to categorize Corwin the same way. One can argue that Corwin involves a reversal of almost 30 years of Delaware doctrine regarding judicial review of actions by boards of target companies. At the very least, Corwin has compelled a deep reexamination of that doctrine.

Under the Corwin doctrine, the Delaware courts will apply the deferential business judgment rule standard of review to decisions of a board of directors of a target company if the relevant M&A transaction is approved by a fully informed, uncoerced vote of disinterested stockholders (other than in a squeeze out, in which MFW applies). The Delaware courts have already substantially elaborated on Corwin by expanding it to provide business judgment rule standard of review if a majority of the stockholders accepted a non-coercive tender offer and by explicitly acknowledging that Corwin is a substantial limitation on two iconic Delaware decisions from the 1980’s: Unocal, dealing with takeover defenses, and Revlon, dealing with directors’ responsibilities when selling a target company.

We have also seen cases in which the Delaware courts have declined to apply Corwin. It is clear the courts will over time develop a coherent theory of what constitutes coercion of stockholders. So far, in one decision, the court found a stockholder vote to be coerced by pre-transaction actions by the board that made the status quo (“no deal”) alternative very unattractive to stockholders. In a second decision, the court did not apply Corwin to an M&A transaction in which a major stockholder received ancillary benefits (echoing MFW). No doubt there will be significant developments in this area.

Corwin has significantly changed M&A practice in the U.S., with deal professionals pushing more aggressively for stockholder votes by disinterested stockholders as well as better disclosure in proxy statements. Corwin’s impact on M&A stockholder litigation has been even more dramatic. In the time since Corwin, there has been a significant drop in U.S. M&A litigation alleging fiduciary duty claims and something of an increase in litigation claiming violations of the U.S. securities laws. Although correlation does not prove causation, the prevailing view of market professionals is that the shift in litigation is substantially attributable to Corwin and related decisions.

Corwin is not a doctrine of stockholder ratification but merely sets the standard of review applied by the Delaware courts. However, given that that standard of review tends to be outcome-determinative, the practical effect of Corwin is very similar to stockholder ratification.

Corwin represents a profound challenge to the U.S. model in M&A transactions. Historically, a key component to the process of holding target boards accountable in M&A transactions has been the combination of searching judicial scrutiny and private litigation as the vehicle for that scrutiny. By allowing business judgment rule deference, the Delaware courts are now saying that “M&A is not different—at least if the stockholders approve.”

So what happened? One explanation is that Corwin is simply the latest effort by the Delaware courts to bring frivolous M&A litigation under control. This view links Corwin to the Trulia decision, in which the Delaware courts signaled an increasing reluctance to accept disclosure-only settlements of M&A litigation and to the decisions upholding “forum selection” by laws. In this view of Corwin, the Delaware courts have taken control of M&A litigation by ensuring that litigation will be in Delaware courts and have substantially limited frivolous litigation through the combination of Trulia and Corwin.

There is another explanation, though, that is more consistent with MFW and the appraisal cases. As one judge said, “there is little utility in a judicial second-guessing of [a determination that a transaction is in the corporate best interest] by the owners of the entity.” That principle reflects a substantial deviation from the Delaware historical view, as evidenced by the Delaware courts’ reluctance to accept stockholder ratification as a defense to a claim for breach of fiduciary duty by directors. In the U.S. director-centric model, the Delaware courts historically have scrutinized the conduct of boards of directors to determine whether it met the standards of care, loyalty and good faith expected of boards of directors, not solely whether the M&A transactions they negotiated were in the best interests of stockholders. Moving to a model in which there is effectively no judicial scrutiny of directors’ conduct with respect to a transaction so long as the stockholders approve that transaction by a fully informed and uncoerced stockholder vote is perilously close, in substance, to a world in which the primary legal responsibility of the target board is to ensure such a vote. That is much closer to the world of the U.K. Takeover Code than to the Delaware world of Unocal and Revlon.

This will be tested. The guiding principle of Corwin stands uneasily next to such decisions as Airgas, in which the Delaware courts have upheld takeover defenses notwithstanding fully informed and uncoerced votes by stockholders against the use of such defenses. As one commentator asked recently, “Can the Delaware courts sustain the position that the board is immune from scrutiny because of stockholder approval but is also immune from scrutiny if it ignores the stockholders?”

Stay tuned.

Reversal of fortunes

It is dominated by mid-sized firms while global players and City leaders lag far behind. Watson Farley & Williams (WFW) sits in the third spot. You must scroll down nearly 40 positions before finding the likes of Linklaters and Clifford Chance.

The power of the ordinary

The growth in regulation has made compliance part of business as usual for companies and most in-house legal departments are fully occupied with the day to day.

Five things general counsel should know about litigation finance

Litigation finance is becoming an increasingly important part of the commercial litigation landscape: according to the 2017 Litigation Finance Survey conducted by Burford Capital, the number of lawyers in the US who said their firms had used litigation finance has risen 414% since 2013. Over half (54%) of UK lawyers who have not yet used litigation finance expect to do so within two years.

Continue reading “Five things general counsel should know about litigation finance”