The widespread deployment of anaerobic digestion facilities is finally becoming a reality after many years of gradual but slow progress. Interest in gas to grid facilities has been a particular feature, prompted by the incentives available under the Non-Domestic Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI). This article explores the regulatory and contractual foundations behind the gas to grid revenue streams and considers some of the practical, commercial and legal issues around the RHI and gas purchase contracts.

BACKGROUND TO THE LAW

The Renewable Energy Directive set a binding target of 20% of the EU’s energy consumption to come from renewable sources by 2020. As part of this legislative agenda, the UK committed to generating 15% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020 and introduced a number of renewable incentive schemes to achieve the target including the RHI.

The published policy objective behind the RHI is to increase the provision of renewable heat to 12% of the UK’s total heat demand by 2020. To achieve this, the RHI supports (through tariff payments) the generation of renewable heat delivered as a liquid or steam. Since coming into effect on 28 November 2011, the RHI has also provided support for the injection of bio-methane into the gas distribution network.

The commercial uptake of gas to grid projects (projects) in the UK has been slow. There are a number of factors which have contributed towards the low deployment figures including (i) the general lack of experience and guidance in relation to the injection of bio-methane into the UK’s gas network; and (ii) some initial hurdles created by the RHI regulations. As at March 2014, only three projects had been commissioned in the UK, with the projects at Didcot, Poundbury and Vale Green being the market leaders. This can be contrasted with the 60 projects already commissioned in Germany and another 60 in the Netherlands.

The position is expected to change quickly. Gas to grid projects are unique under the RHI regime, in that they do not require a physically adjacent offtaker. Rather, due to the gas network a developer can feasibly sell its bio-methane to shippers across the UK. This removes one of the key obstacles to investment; finding a creditworthy offtaker for a 20-year period. It is no surprise then that Ofgem is currently processing three1 gas to grid applications and a number of other developers are looking to reach financial close on gas to grid projects within the next few months.

GAS TO GRID BASICS

The basic premise of RHI supported gas to grid projects is that biogas is produced from a biomass feedstock source (such as food waste or other organic material) that is (when treated to produce bio-methane) equivalent to natural gas (used by consumers on a daily basis) and that bio-methane is injected into the gas distribution network.

There are currently two main ways by which developers can produce the biogas: anaerobic digestion or gasification. In both cases, the resulting biogas does not usually meet the UK’s gas safety and quality requirements as set out primarily in the Gas Safety (Management) Regulations 1996. This is due to the biogas containing impurities such as hydrogen sulphide and carbon dioxide and failing to meet the required calorific value. As a result, after production, the biogas is upgraded by removing the impurities, blending it with propane (to increase the calorific value) and odourising it (for safety), to ensure the bio-methane can be injected into the gas distribution network. The basic process is show in the diagram overleaf.

REGISTRATION/PRELIMINARY REGISTRATION

As with any renewables project, whether funded on or off balance sheet, knowledge of and security around the eligibility of a project and the level of support it will receive are vital for developers and funders.

The RHI does not currently provide developers and funders with any certainty that a project is eligible for support until that project has been commissioned and bio-methane is being injected into the gas distribution network.

Accordingly, the government’s recent proposal to amend the RHI (through the Renewable Heat Incentive Scheme (Amendment) Regulations 2014) to enable projects to obtain preliminary registration where they have entered into a Network Entry Agreement is a welcome development. Preliminary registration will help to give stakeholders certainty that their project is eligible for support before significant capital sums are committed.

However, the RHI does not enable developers to ‘secure’ an RHI tariff in advance of a project being constructed. The RHI has an inbuilt quarterly tariff degression mechanism which provides for tariff levels for newly accredited facilities to be reduced (when compared to historic tariff levels) if certain levels of deployment are met both under a particular technology band and under the RHI as a whole. To alleviate the uncertainty this causes to developers the Department of Energy and Climate Change publishes monthly and quarterly RHI budget forecasts which provide developers with some degree of visibility as to when a tariff degression may occur. Given the potential number of projects in the pipeline, it will become increasingly important to analyse this data.

GAS MARKET OVERVIEW

The gas market is heavily regulated and controlled, containing a myriad of legislation, best practice and codes which developers are expected to understand and put into effect. The main parties within the gas market who are all licensed by Ofgem (apart from gas producers who produce bio-methane) are:

- Producers, who produce the gas which enters into the gas distribution system. Historically these have been large offshore producers (eg BP and Shell, with a number of smaller offshore players recently coming into the market). With the impending shale revolution and the expected increase in the quantity of gas to grid projects coming online, the make-up of this group is likely to change.

- Gas transporters, who own and operate the gas network in the UK (the gas distribution network and gas transmission network) and transport gas from producers to the end consumer using their infrastructure. Gas transporters are also usually responsible for quality testing of gas and gas metering. Gas transporters include Wales and West Utilities, Southern Gas Networks, National Grid, Northern Gas Networks and smaller independent gas transporters who typically install and operate their own pipeline system on new housing and commercial developments;

- Gas shippers who purchase capacity on the gas network from gas transporters and covey gas to consumers using that capacity. More broadly, gas shippers contract with producers to bring gas into the gas network and subsequently act as the wholesale merchants of that gas to gas suppliers;

- Gas suppliers who sell gas to domestic and non-domestic consumers. Gas suppliers include the majority of the well-known retail energy companies ie Npower, EDF and SSE and a number of other smaller entities who sell gas to consumers in specific circumstances. Importantly a company can be both a gas shipper and a gas supplier;

- Ofgem, who licenses and regulates the gas market (focusing particularly on economic regulation and the protection of consumers); and

- The Health and Safety Executive, who have overall responsibility for health and safety in the gas sector.

REQUIRED CONTRACTUAL AGREEMENTS

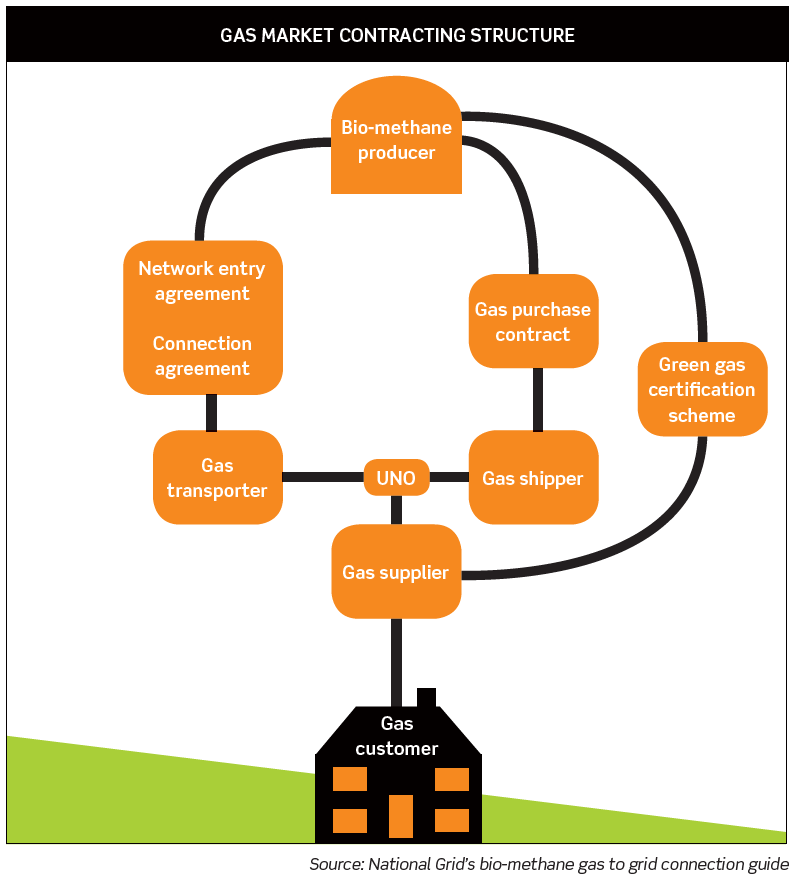

As a result of the complicated structure of the gas market, developers will need to enter into a number of commercial agreements with different parties to ensure their bio-methane reaches the market. These include:

- a network entry agreement with a gas transporter which sets out the technical and operational conditions of the connection between the gas transporters’ gas network and the project including the gas quality requirements, the maximum permitted flow rate of bio-methane from the project into the gas network and ongoing charges the gas transporter will invoice the developer. While considerable effort has been made by gas transporters to standardise these agreements, the specific (and in some cases the general) terms of network entry agreements are being developed on a case-by-case basis. Accordingly and given the indefinite duration of these agreements and the severe consequences of an adverse network entry agreement, developers should ensure that the agreement is technically and legally acceptable. Key areas are flow rate guarantees, the closing of the network entry valve, one party’s liability for another’s costs as a result of changes to the gas network and/or a project and general liability limits. As the network entry agreement is proposed to be a requirement for preliminary registration and is required to be nearly finalised when negotiating any gas purchase contract, developers will look to sign up to these agreements at an early stage.

- a gas connection agreement with a gas transporter which sets out the contractual arrangements to proceed with the detailed design and build of the connection works between a project and a gas transporter’s distribution network. The connection agreement usually sets out both parties’ obligations for the onsite works associated with the physical entry connection into the gas distribution network. A developer may have the option to appoint an independent connection provider to carry out some of the grid connection works which could help to reduce timescales and costs.

- a gas purchase contract with a gas shipper whereby the producer sells its bio-methane to a gas shipper and is subsequently permitted to inject the bio-methane into the gas distribution network. Like electricity grid regulation, a developer cannot inject gas into the gas distribution system unless it has a contract with a gas shipper for that bio-methane (equivalent to a power purchase agreement with an electricity supplier). The terms of a gas purchase contract have a substantial effect on a developer’s project revenue (along with RHI tariff payments), and, as a result, developers should carefully review the terms and conditions of any contract, as well as the general commercial principles. Term, payment terms, the credit rating of the gas supplier/credit support, change in law, termination and imbalance provisions are key areas. As bio-methane gas purchase contracts are starting to develop (gas shippers usually purchase gas in daily quantities nine to ten times greater than most projects’ daily bio-methane output) and new entrants are entering the market, there is genuine scope for a developer to negotiate commercial and legal terms.

The diagram below sets out the route to market contracting structure.

In addition to the agreements above, any project will also require a number of other commercial agreements, permissions and licences to ensure on-going commercial operation.

These include planning permission for the project (which should usually include any grid connection works), an option and lease, feedstock agreement/fuel supply agreement, operation and maintenance agreement(s) for the anaerobic digestion/gasification plant, bio-methane upgrading equipment and any gas storage facility, a digestate offtake agreement, an environmental permit and a propane supply agreement. Importantly though, the implementation of the Gas Act 1986 (Exemption) (Onshore Gas) Order 2013 means that developers do not now need to obtain a gas transport licence to cover the transfer of bio-methane from a project site to the gas network.

As all the agreements described above will form an important part of any project investment decision, careful consideration should be given as to how and when the agreements are finalised. While gas to grid developers have greater offtake security when compared to heat projects in that they have the ability to sell bio-methane to any gas shipper, funders may require a full contract suite to be finalised before making an investment decision. Accordingly, many developers will commence contract negotiations as soon as a planning application has been submitted.

BIO-METHANE REVENUE STREAMS

A project is likely to have between two and four direct revenue streams.

RHI payments

Under the RHI, once a bio-methane producer is registered, it secures a 20-year tariff which rises in line with the retail prices index.

The current RHI tariff support level for gas to grid projects is 7.5 pence per kWh (subject to RPI adjustment) for all project capacities (with 1 kWh equating to roughly 3.4 cubic feet of bio-methane).

Ofgem currently calculates a project’s quarterly RHI payment (and pays it quarterly in arrears) by taking into account the following variables:

- the volume and gross calorific value (GCV) of bio-methane injected into the gas network during a quarter by a project;

- the GCV of the propane and volume of propane that was contained in the bio-methane;

- any heat supplied to the bio-methane production process during that quarter;

- any heat supplied to the biogas production plant from an ‘external’ source (ie any source other than from the combustion of the biogas) during that quarter; and

- (in relation to bio-methane produced from contaminated feedstock via gasification/pyrolysis only) the contamination percentage of the feedstock (ie the fossil fuel proportion of the feedstock). This figure will be deducted from 100% to give the ‘proportion of biomass contained in the feedstock’ which is part of the payment calculation for bio-methane producers.

In general terms, Ofgem subtracts all the other variables from (a) to produce a quantity which is multiplied by the applicable tariff rate.

Stakeholders will be closely following the Department of Energy and Climate Change’s current review of the bio-methane injection tariff, as its initial analysis indicates that it is likely to introduce a tariff capacity limit to ensure projects with large flow rates are not supported to excess and do not exhaust rapidly the budget allocated.

Bio-methane sales

In addition to the RHI support payments as described above, developers will also enter into a gas purchase agreement with a gas shipper for the bio-methane. The commercial options for such gas purchase contracts (from a bio-methane perspective) are likely to expand rapidly as the market develops.

Green gas certificate sales

As mentioned in our September 2013 ‘Greening your Gas’ article, Green Gas certificates are a the result of two new (currently voluntary) schemes, which provide an audit trail enabling developers and consumers to demonstrate the renewable provenance of the bio-methane. Where a developer subsequently subscribes to either the Bio-methane Certification Scheme or the Green Gas Certification Scheme it will be issued with certificates in proportion to the volume of bio-methane injected into the gas network. While these certificates have no statutory imposed value, they may start to accrue a monetary value as a result of consumers’ being willing to pay more for certified green gas. It remains to be seen though whether a mature market will develop for green gas certificates.

Transport discount

Where a project is connected directly to the gas distribution network (as opposed to the transmission network) the gas shipper that has purchased a project’s bio-methane will usually receive a gas distribution network transport discount/rebate (contingent on the charging methodology of the gas transporter and a number of other variables). As a result, developers and gas shippers have generally shared the discount/rebate which can be worth significant amounts.

Finally, while not directly related to the bio-methane, a number of developers have also been able to sell the digestate produced by their projects to third parties as organic fertiliser, although in many cases developers will assume in their financial models that the digestate will be taken by a third party at no cost.

CONCLUSION

Gas to grid projects and the bio-methane market have commercially arrived. The unique credit security of gas to grid projects under the RHI and the proven technology track record is causing ever greater interest in the sector. The proposed legislative amendments to the RHI allowing for preliminary registration should help to enhance the level of interest still further.

Putting together a gas to grid project is less straightforward than many other types of renewable projects due to the number and nature of the commercial agreements that need to be tied up and the relative infancy of such projects in the UK. With sound legal, commercial, and technical advice these challenges can be overcome and for those that do so successfully, the potential rewards can be great.