The decision in Bartoline v Royal Sun Alliance [2006] has some commentators arguing that the door has effectively been shut on recovering environmental liabilities under public liability (PL) policies. This article examines whether this is true; it looks at the legal principles in Bartoline, its impact on the environmental insurance market and the likely future of the PL insurance market in the UK.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MARKET

The development of environmental insurance in the UK began in the 1970s and 1980s, but was somewhat of a slow starter in comparison with the US. The environmental insurance market in the UK has since developed rather cautiously, owing to a lack of competition in offering UK-focused environmental policies (with most reflecting US practice) and with many companies believing that they were still comprehensively covered by PL policies.

The key milestone for environmental coverage under most PL policies was the introduction in 1991 of pollution exclusion wordings pursuant to the Association of British Insurers guidelines and/or the Lloyds NMA 1685 clause, such that only pollution as a result of a ‘sudden identifiable… incident’ is covered – ie ‘gradual’ pollution is excluded. While some policy holders are more conscious of environmental risks and elect to negotiate a specialist environmental insurance policy, others have simply relied upon their PL policy for indemnification against all environmental liabilities. However, with the introduction of the pollution exclusion wording and the decision in Bartoline, recovery under PL policies has become increasingly complex.

THE FACTS

In May 2003, a fire broke out at Bartoline’s factory where it carried out the manufacturing and packaging of solvents and wood preservatives. The fire resulted in the pollution of two local watercourses, which led the Environment Agency (EA) to incur costs of over £600,000 on the clean-up and associated works. The EA subsequently claimed this sum from Bartoline pursuant to s161 of the Water Resources Act (WRA) 1991. In addition, Bartoline incurred around £150,000 of costs, in complying with an EA works notice (also issued under s161 WRA 1991). Bartoline was insured under a PL policy and subsequently sued its insurers (RSA), in order to recover both sums (after their initial claims were rejected).

THE DECISION

The liability to pay the £600,000 to the EA was not a liability to pay ‘damages’ (as per the wording of the policy); instead it was held to be a liability to pay a debt under a statute. In addition, the indemnity against ‘legal liability for damages’ under the PL policy did not include Bartoline’s expenditure in respect of the EA works notice. In its judgment, the Court differentiated between the EA’s powers under statute and the common law of tort, stating that ‘one arises out of the need to protect the public interest in the environment and the other to protect individual interests in property’. There was subsequently an appeal against this judgment. Interestingly, this was settled out of court (confidentially) before being heard.

COMMENT

Revisiting Bartoline: outcome?

If the decision in Bartoline was to be revisited, what would be the likely outcome? This is, of course, fact dependent and it is important to note that PL policies may have varying terms, conditions and definitions and therefore, must be analysed on a case-by-case basis (indeed, some PL policies may respond, in spite of the decision in Bartoline).

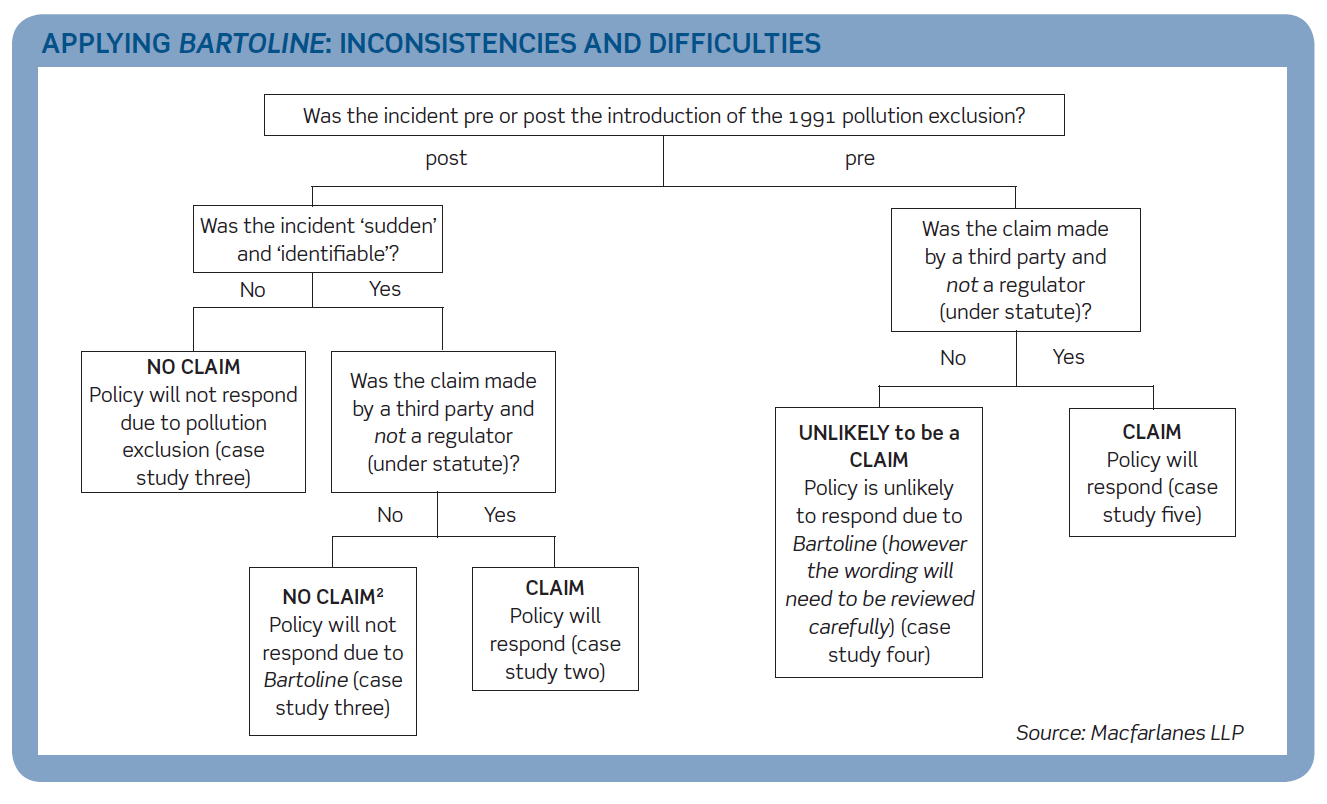

It is entirely arguable, and many commentators would agree, that the decision is flawed. Fundamentally, there are a number of inconsistencies and difficulties evident when the decision is applied in the context of environmental law, particularly highlighted by the flow chart and case studies below1.

Revisiting Bartoline: practical perspective

It is not in the insurance industry’s interests for the courts to revisit Bartoline – it was rather telling Bartoline was confidentially settled out of court. Indeed, would we be writing this article had the appeal been heard? Bartoline makes it significantly more difficult to claim under PL policies for environmental liabilities. Furthermore, many PL providers now offer extensions to their PL policies (aptly named ‘Bartoline extensions’ or statutory clean-up costs extensions). It has also given other insurers the opportunity to promote more comprehensive environmental liability policies. For example, in respect of case study one below, if a ‘Bartoline extension’ was included in the applicable PL policy (presumably at a higher premium), the factory owner would potentially be able to make a claim. However, these extensions are, as yet, legally untested so their effectiveness is still uncertain.

The UK market: a restriction?

If Bartoline was to be revisited, the outcome would be difficult to predict, given the inconsistencies in the original decision and the necessity of a case-by-case approach, driven by the wording of each individual PL policy. This is in stark contrast to the US, where a more litigious environment would have been a bigger driver to pursue a re-evaluation of the case more aggressively. The principles decided under Bartoline, in respect of PL insurance policies and the uncertainties in cover that exist, have restricted both the expansion of the UK environmental insurance market and potentially the practice of insurance archaeology. The UK market is, however, beginning to follow in the footsteps of the US, particularly given the increasingly rigorous enforcement of environmental legislation by regulators in the UK.

CONCLUSIONS

Until the fundamental legal principles under Bartoline are revisited (which would aid in the development of the UK environmental market), businesses seeking cover for environmental liabilities should either do so by negotiating an extension to their PL cover or by purchasing an environmental liability policy, and at the very least, seek adequate advice as to the cover provided under existing insurance policies.

NOTES

- For the purposes of the case studies, it is noted that any notification procedures that may be present in PL policies and other evidential issues that could arise, have been disregarded, in order to clearly illustrate the difficulties.

- As discussed above, there may be a claim in this instance, where the PL policy contains a ‘Bartoline extension’.

CASE STUDY ONE: NO CLAIM

A fire at a factory in 2011 leads to pollution of a privately owned river. The EA undertakes emergency works to the river and subsequently claims the costs of such emergency works from the factory owner, under statute. The factory owner is not able to claim under a PL policy:

- the incident is sudden and identifiable and therefore not excluded by a pollution exclusion clause; however

- the claim by the EA is not a claim for ‘damages’, but a liability to pay a debt under statute (Bartoline).

CASE TWO: CLAIM

A fire at a factory in 2011 leads to pollution of a privately owned river. The riparian owner cleans up the river and subsequently sues the factory owner for costs of the remediation. The factory owner is able to claim under a PL policy:

- the incident is sudden and identifiable and therefore not excluded by a pollution exclusion clause; and

- there is a third-party claim for damages.

CASE STUDY THREE: NO CLAIM

In 1998, a factory owner removes an underground storage tank, used since 1992 for storing petroleum. In 2013, a neighbouring land owner discovers petroleum has contaminated their land, which is found to have gradually leaked from the factory owner’s underground storage tank before its removal and migrated onto their land. The neighbouring owner subsequently cleans up their land and sues the factory owner for the costs of the remediation. The factory owner is not able to claim under a PL policy:

- there is a third-party claim for damages, so this does not fall foul of the principles under Bartoline; however

- the pollution was gradual and occurred after 1991 when the pollution exclusion was incorporated into PL policies and so the policy will not respond regardless of whether the claim is by a third party or a regulator.

CASE STUDY FOUR: UNLIKELY TO BE A CLAIM

In 1988, a factory owner removes an underground storage tank, used for storing petroleum. In 2013, a neighbouring land owner discovers petroleum has contaminated their land, which is found to have gradually leaked from the factory owner’s underground storage tank before its removal and migrated onto their land. The EA undertakes emergency works to the land and subsequently claims the costs of such emergency works from the factory owner, under statute. The factory owner is unlikely to be able to claim under a PL policy:

- the pollution was gradual, but clearly occurred before 1991 when the pollution exclusion was incorporated into PL policies (practically, there may be a difficult evidential issues in such a case); however

- the claim by the EA is not a claim for ‘damages’, but a liability to pay a debt under statute (Bartoline).

However, the wording of each individual policy must be carefully reviewed, as there may be wording to the effect that the policy will respond.

Case study five: claim

In 1988, a factory owner removes an underground storage tank, used for storing petroleum. In 2013, a neighbouring land owner discovers petroleum has contaminated their land, which is found to have gradually leaked from the factory owner’s underground storage tank before its removal and migrated onto their land. The neighbouring owner subsequently cleans up their land and sues the factory owner for the costs of the remediation. The factory owner is able to claim under a PL policy:

- the pollution was gradual, but clearly occurred before 1991 when the pollution exclusion was incorporated into PL policies (practically, there may be a difficult evidential issue in such a case); and

- there is a third-party claim for damages.