Whilst few product recalls grab the headlines in the way of Toyota’s worldwide recall of millions of Prius and other vehicles, product recalls are happening all the time as can readily be seen from newspapers, store advertisements, government agency announcements and a variety of other media. Barring rare cases of malicious tampering, each recall represents a breakdown of risk management, whether in design, manufacture or packaging, in communicating necessary information about the product’s characteristics, or in foreseeing ways in which a product might be innocently misused.

The recalls that do have a high profile shine a powerful light on how damaging these failures can be – not just potential injuries for consumers and others at risk – but to the reputations of the companies responsible for the products and the value of their brands. The legal consequences are becoming increasingly damaging too. In June 2009 the toymaker Mattel agreed to pay $2.3m in civil penalties in the United States for violating a federal lead paint ban that led to the recall of millions of its Barbie, Dora the Explorer and other popular toys in 2007. A Japanese court sentenced four former senior executives at Mitsubishi Motors to three years imprisonment (suspended for five years) for the death of a truck driver after covering up vehicle defects in one of that country’s biggest safety scandals. In the United Kingdom in 2007 confectionery producers Cadbury’s were handed criminal fines totalling £1m for breaches of food safety legislation that led to the recall of seven products in its chocolate range. In China severe penalties were handed down in January 2009 after the contaminated milk scandal involving misuse of the industrial chemical melamine, including death sentences and life imprisonment for some of those responsible.

The difficulty of the challenge facing managers suddenly tasked with a product safety crisis has been compared by one leading commentator to driving a car backwards at speed with little warning. In most developed countries the days are gone when companies could internalise the information about the known dangers in their organisations and quietly manage the problem with what has been called a ‘silent recall’ – the removal of existing stocks of defective products. Globalised markets, higher consumer safety expectations and tighter legislation have made the processes of crisis management considerably more transparent. As well as having to deal with notifying government officials, putting the supply chain into reverse, publishing warnings and managing the logistics of restocking and resupplying large numbers of customers, there is the public admission of failure to be faced, and the threat of mass tort actions as well as regulatory penalties. Managers can be forgiven for thinking when contemplating recalls that they are damned if they do, and damned if they don’t.

Many large companies operating in major economies nevertheless still undertake only the most rudimentary recall planning. Where preparations are made the emphasis is often on damage limitation for the brand and public relations strategies. Communications and government relations consultants have developed specialist units that can assist with these functions. There is no doubt that these are critical considerations, sometimes affecting the very survival of a business. The legal and insurance aspects of recalls are often less well anticipated and understood. The need to obtain experienced legal advice early on in product crises has never been greater.

There has been a rapid growth in regulatory oversight of product recalls. But, at the same time, this has increased the diversity internationally in the laws governing questions such as when a product defect is deemed to require notification to national authorities, how that information is dealt with, and how prescriptive the procedures are for deciding on and managing the various steps to be taken after the need to address a defect has been identified.

THE UNITED STATES

The most highly developed laws in this area are probably those found in the United States, whose Consumer Products Safety Commission (CPSC) was established in the 1970s and where there have long been duties on manufacturers and others responsible for supplying products to notify the authorities when their products do not meet safety standards or might have defects posing substantial risks to consumers. As with many other countries, the precise requirements vary from product to product. A number of other different sector-orientated regulators for products (eg food, tobacco and motor vehicles) sit outside the remit of the CPSC. The Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act 2008 has overhauled consumer protection law generally in the US and, among other things, provides for uniform information in recall notices, the establishment of an online hazards database, enhanced powers for the CPSC to dictate how recalls or other corrective actions will be carried out and increased penalties for violations. The Act also now permits the CPSC to share confidential product safety information with foreign governments and agencies.

EU REGULATION

In Europe the obligations of manufacturers and others in the supply chain were made clearer and more consistent across the EU member states by important revisions to the General Product Safety Directive taking effect from 2004. To promote traceability, Decision 768/2008/EC now positively requires the name and address of manufacturers and importer of products placed on the market in the EU to be indicated on the products themselves, or, where that is not possible, on packaging or other documentation.

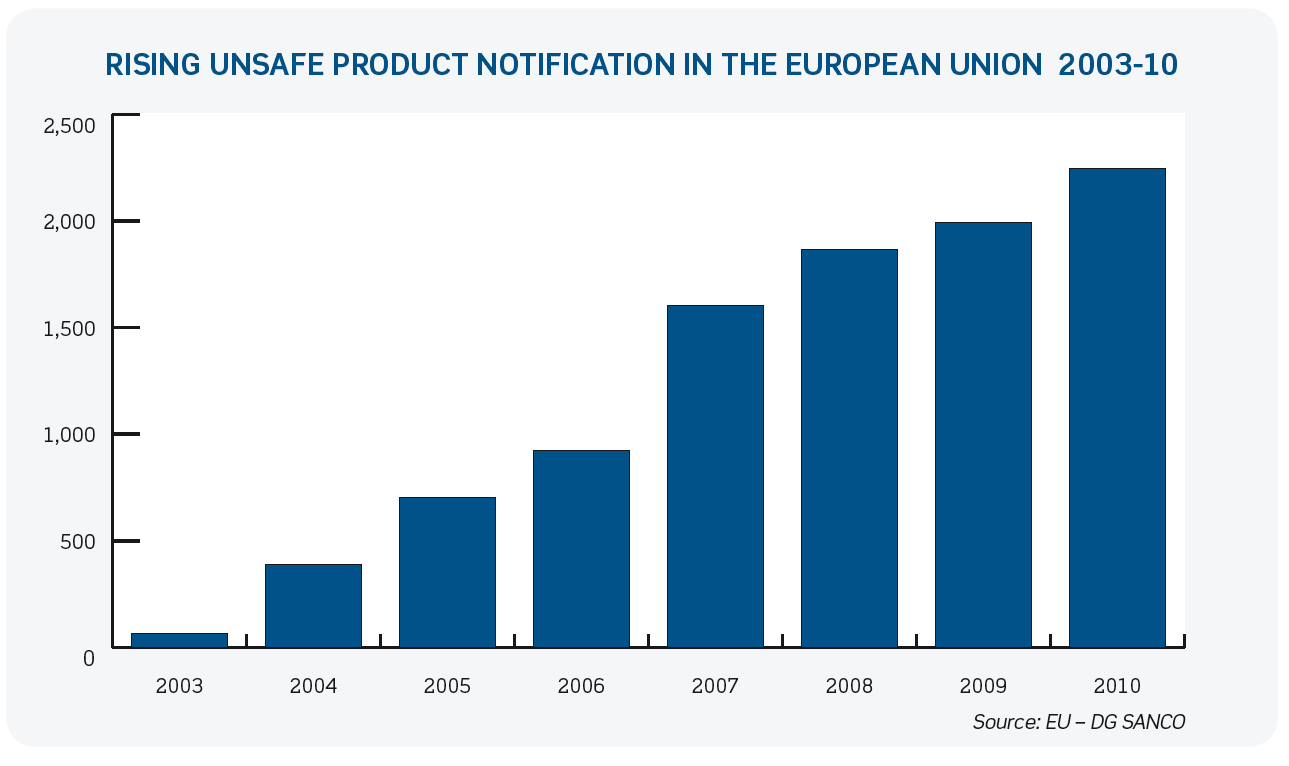

The EU’s 2010 Annual Report shows how awareness of these obligations, which require the notification of unsafe products, has increased considerably during this period (see chart below). In 2010 there was an increase of 15% over 2009 in measures taken against unsafe products and reported through RAPEX, the EU rapid alert system for dangerous consumer products. These notifications are ones that have been transmitted by the EU to authorities across the 27 member states, and details of the products are published on the RAPEX website.

The European authorities are now being required to go even further to improve capabilities to meet more consistent minimum standards of market surveillance and enforcement by Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 (which is part of a package of measures contained in what is known as the New Legislative Framework). The measures also include stronger border controls to detect non-compliant products. Aside from consumer protection, one justification given for these measures is levelling the playing field for compliant businesses. It would appear that the growth in European recalls will continue. As a consequence of this growth, new guidelines for the management of RAPEX and member state information sharing measures have been published in Decision 2010/15/EU, including a new risk assessment methodology for determining the seriousness of product defects and the need for urgent action.

GLOBAL TRENDS

While the trend is towards increased regulatory intervention generally in developed nations, the pace of change is different in other regions, especially Asia. Japan, for example, has had recall laws for a number of years, but it was only at the end of 2006 that it introduced binding rules for notification of ‘serious product accidents’ with defective consumer products to its authorities, and authorised the publication of this information by them. This threshold for notification – actual accidents – is much higher than in the United States or Europe, which require there only to be a risk of injury, and only manufacturers and importers are subject to the duty. Japan has however increased its authorities’ powers to dictate recall measures.

A number of international bodies exist with objectives of increasing the effectiveness of information sharing and joint enforcement, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) committee on consumer policy (CCP), the International Consumer Product Safety Caucus, the International Consumer Product Safety and Health Organisation, the Product Safety Enforcement Forum of Europe and the committee on consumer policy of the International Standards Organisation.

The significant number of recalls involving products of Chinese origin (58% of European RAPEX notifications in 2010) has led to recognition of the need for international liaison with the authorities in China. The EU, United States and Japan have memoranda of understanding with the Administration for Quality, Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China for information sharing and co-operation in addressing problem products. There are also other bilateral agreements among them, and protocols such as the US/EU guidelines for information exchange and on administration cooperation, and AUZSHARE, a computerised database on enforcement matters for the Australian and New Zealand authorities.

The direction of travel for international policy in this area can be discerned from the conclusions reached at a roundtable meeting of regulators, business representatives and other stakeholders from around the world hosted by the OECD in October 2008. This concluded that there is need for greater inter-governmental co-ordination and co-operation, harmonisation of product safety standards, a more proactive approach to product safety failures, increased resources available to regulators, and a rapid international information exchange system to enable countries to notify each other about the presence of unsafe goods in markets.

Finally, readers interested in global trends in product safety and recalls and comparisons between national legal and enforcement regimes will find useful information in the recent study produced for the OECD’s CCP entitled Analytical Report on Consumer Product Safety, and another report entitled Enhancing Information Sharing on Consumer Product Safety, both available atwww.oecd.org

Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research. This article was first published in Getting the Deal Through – Product Recall 2011, (contributing editor Mark Tyler of Shook, Hardy & Bacon). For further information please visit www.GettingTheDealThrough.com