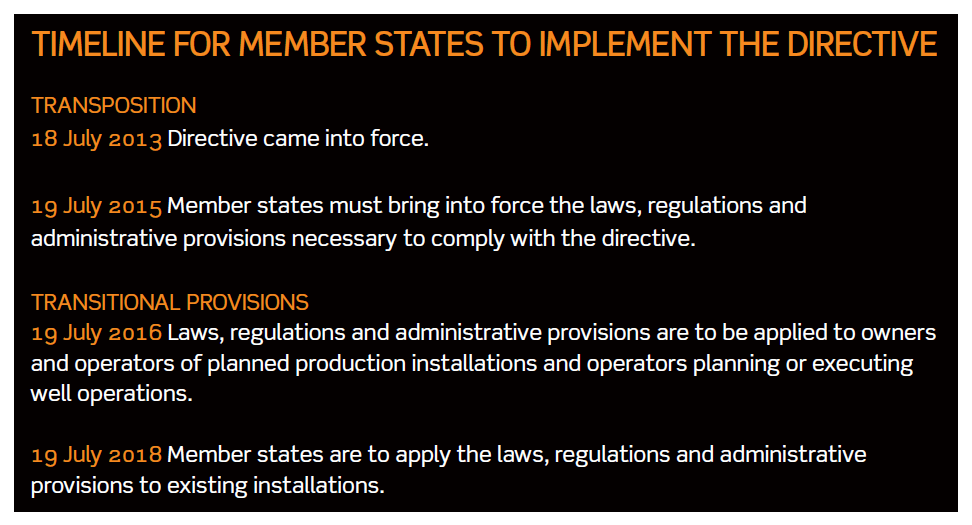

In the wake of the Macondo oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the new EU directive in respect of safety of offshore oil and gas operations is now in force and a timescale has been fixed for it to be transposed into UK law by UK legislation. It sets out the minimum conditions for safe offshore oil and gas operations and for reducing the consequences of any major accidents that occur. The Directive will apply to future offshore oil and gas installations and operations and, after a slightly longer transitional period, will also apply to existing installations.

BACKGROUND

Following Macondo, the European Commission (the Commission) reviewed its existing framework of policies, as well as offshore oil and gas operations. There was a view that the existing regulatory framework was fragmented and divergent and did not provide adequate assurance that the risk of offshore accidents is minimised throughout the Union, nor that, in the event of a spill occurring, the most effective response would be deployed in a timely manner with clear responsibilities and liabilities for cost/damage clean-up. The Commission therefore concluded that ‘the likelihood of a major offshore accident in European waters remains unacceptably high’.

Its initial response to these findings was a draft regulation that was published in October 2011.

The regulation would have applied to all member states (as well as Norway) and had the effect of centralising control of offshore health and safety and environmental protection in Europe. The Commission recognised and applauded the extremely high safety standard of North Sea oil producing countries and in fact ‘cherry picked’ from the various regimes – particularly the UK – to produce the draft regulation. Its intent was to ensure that all of the other EU countries conducted offshore operations to the same standard.

However, the proposed regulation caused concern in some quarters as there was a view that it might not establish a ‘goal-setting’ framework and would not therefore take account of one of the critical changes introduced by the UK government following the Cullen Inquiry into the Piper Alpha disaster. Furthermore, it would ultimately have meant significant and costly changes would have been required to re-write existing regulation, even for those countries with ‘gold standard’ safety regimes that between them produce over 90% of European oil and gas (the UK, Netherlands, Denmark and Norway).

The proposed regulation also received strong criticism from some due to unrealistic timeframes for implementation as well as poor drafting and a lack of interpretative guidance, which it was claimed could cause confusion and hinder operations until there was greater certainty. It is therefore unsurprising that the proposal for a regulation in itself and the proposed regulation content were challenged with strong opposition from both the UK government and Oil & Gas UK (OGUK).

This culminated in various proposals and calls for a more flexible directive from OGUK, the International Association of Drilling Contractors (IADC) and others. The Commission relented and on 28 June 2013 Directive 2013/30/EU was published in the Official Journal and came into force 20 days later.

The directive has been welcomed by the UK oil and gas industry. Robert Paterson, OGUK’s health, safety and employment director confirmed that OGUK:

‘… believe the directive will be the best way to achieve the objective of raising standards across the EU to the high levels already present in the North Sea’.

It has the benefit of allowing each member state’s government to control how it implements its terms – providing they reach the required outcome. This allows the UK (and the other key North Sea oil and gas producing countries) to simply enhance its existing, world-class safety regime rather than re-inventing the wheel – and potentially undoing years of experience and lessons learned.

OBJECTIVES OF THE DIRECTIVE

The key overarching objectives of the directive are:

- to prevent as far as possible the occurrence of major accidents and potential oil spills resulting from oil and gas operations;

- to establish minimum conditions for the safe exploration and production of oil and gas, thereby increasing protection of marine environments against pollution;

- to improve the response in the event of an incident; and

- where prevention is not achieved, for clean-up and mitigation to be carried out to limit the consequences.

Member states must require operators to follow certain general principles of risk management in respect of their offshore oil and gas operations that include taking all ‘suitable measures’ to prevent major accidents in offshore oil and gas operations and limit consequences for human health and the environment in the event of a major accident.

Operators must also be required to ensure that the residual risks of major accidents to persons, the environment and offshore installations are ‘acceptable’, which is defined as:

‘… a level of risk for which the time, cost or effort of further reducing it would be grossly disproportionate to the benefits of such reduction… regard shall be had to best practice risk levels’.

In addition, and crucially, the directive provides that operators are not to be relieved of their duties under the directive due to actions or omissions leading or contributing to major accidents by their contractors.

While there is significant responsibility on operators, there is also an increased onus on licensees – particularly with regard to financial capability – with the aim of ensuring that licensees are financially capable of dealing with the prevention and remediation of a major accident. This echoes the guidelines set out by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) earlier this year.

There are certain key areas that the UK may need to develop in order to comply with the directive, including the following.

Regulatory bodies

The directive prescribes that each member state must have ‘competent authorities’ to regulate and oversee the various safety and environmental regulatory functions that it requires. In order to ensure that there is no conflict of interest, these competent authorities must be independent from those that deal with the economic development of offshore natural resources.

The UK already has the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), which assumed responsibility for offshore oil and gas health and safety following recommendations in the Cullen Inquiry following the Piper Alpha disaster. However, DECC has the dual role of promoting and seeking to maximise the exploration of oil and gas resources in the UK continental shelf (UKCS) as well as regulating oil and gas developments – both from an economic and environmental perspective. As such, a potential conflict in respect of DECC’s roles exists and there may well be a change to its powers so that it no longer handles certain environmental regulatory functions, which would then be passed to another regulator. That regulator will presumably have a greater role to play given the more stringent environmental requirements introduced by the directive.

Reporting on major hazards

Operators must report on major hazards for installations before operations start and ensure that this information is updated over time when appropriate or so required by the competent authority. A thorough review will need to be conducted at least every five years and the results must be notified to the competent authority. The key change for the UK is that the report must consider both safety and the environment. Current UK reporting requirements only extend to safety and we will, therefore, potentially see a revision to the Safety Cases: Offshore Installations (Safety Case) Regulations 2005 to include environmental considerations.

Financial responsibility

Decisions on granting or transferring licences must take into account the applicant’s capability to meet its financial liabilities for operations under the licence and the directive. This therefore includes having the financial capability to deal with a major accident – including remediation and third-party claims. The licensing authority must consult with independent safety and environmental competent authorities before granting a licence and must not grant one unless the licensee has or will make adequate provision to cover their potential liabilities.

In addition, operators are to ensure they have access to sufficient physical, human and financial resources to prevent accidents and limit the consequences of such accidents and licensees are to maintain sufficient capacity to meet their financial obligations resulting from potential liabilities.

It is unclear how these provisions will function in practice and to what extent licensees could be required either by their operators or DECC to ring-fence funds. DECC issued a guidance note which took effect on 1 January 2013 that prescribed what evidence of financial responsibility must be submitted by each co-venturer with applications for consent to drill wells together with methods of estimating potential liabilities. While the guidelines are not law, DECC is unlikely to issue consent without sufficient evidence being provided. However, we will now potentially see even more stringent financial covenant checks against licensees – both by the competent authority and operators of assets.

This may become clearer through the course of 2014 as the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union have required the Commission to undertake further studies and analysis of what appropriate measures may be needed to ensure an adequate liability regime is in place in the event of an accident and, in addition, what requirements in respect of financial capability may be appropriate – including the potential provision of financial security.

Environmental liability

The directive amends the 2004 Environmental Liability Directive (2004/35/EC) to extend the scope of liability to include damage to waters within the entire UKCS. This was previously restricted to territorial waters (ie up to 12 nautical miles) so this change is potentially very significant and could impact upon the insurance industry in terms of availability and cost. Member states must put this into effect by 19 July 2015.

A further change is the requirement for licensees to be directly financially liable for the prevention and remediation of environmental damage. It will be interesting to see whether OPOL (Offshore Pollution Liability Agreement) type arrangements are extended to include non-operator licensees – and whether this will be voluntary or compulsory.

Emergency response

Operators (or owners, as appropriate) must prepare and submit emergency response plans to the competent authority – taking into account the risk assessments undertaken as part of the major hazards reporting and including an analysis of the oil spill response effectiveness. In addition, member states are to prepare (in co-operation with operators) emergency response plans covering all offshore oil and gas installations or connected infrastructure within their jurisdiction.

In the event of a major accident – or in the case of the immediate risk of one occurring – operators (or, if appropriate, the owners) will be obliged to notify relevant authorities and the member state must ensure that the operator (or owners) take all ‘suitable measures’ to prevent its escalation and to limit its consequences – both from a health and safety perspective and in respect of potential environmental damage.

Currently in the UK, operators are required to submit Oil Pollution Emergency Plans (OPEP) to DECC, which must set out:

‘… arrangements for responding to incidents which cause or may cause marine pollution by oil, with a view to preventing such pollution or reducing or minimising its effect’.

The requirements were made more stringent following ‘Exercise SULA’ – an exercise off the coast of Shetland led by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency to test how authorities would react to and deal with a major deep water spill in the UK – and recommendations by the Oil Spill Prevention and Response Advisory Group (OSPRAG), which was formed by OGUK after Macondo. However, in light of changes to the geographical cover extending the environmental liabilities well beyond the territorial sea, this will become more onerous and therefore of greater relevance to operators.

It may well be that the safety case (currently submitted by the operator to the HSE) could change to being a ‘safety and environmental case’ for consideration by HSE as well as the new environmental competent authority.

Presumably the UK government, HSE and DECC will shortly consult with regard to incorporating the directive into UK law in order to meet the required timelines set by the Commission. In the meantime, given the wide application of the new directive, both operators and non-operator licensees will need to give consideration as to how they will address its implications.

The full Directive 2013/30/EU can be found at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:178:0066:0106:EN:PDF.

By Rhona McFarlane, associate, Brodies LLP.

E-mail: rhona.mcfarlane@brodies.com.