EU Emissions Trading scheme (ETS) market reform is taking shape and appears to be moving ahead despite historic inertia. The Energy Savings Opportunity Scheme (ESOS), the new energy reporting regime, is now in place and enforcement of the Carbon Reduction Commitment (CRC) Energy Efficiency Scheme for phase 2 is intensifying. These enhanced requirements are impacting businesses from a compliance and costs perspective. This article reviews some of the new requirements under these regimes, and identifies challenges and nuances businesses may want to consider when updating or developing their corporate compliance policy or sustainability programmes.

BACKGROUND: UK SCHEMES

The EU ETS was the first emissions reduction regime to be put in place. It is a market mechanism intended to abate emissions and incentivise the development of more efficient energy technologies via cap and trade. This regime applies to energy-intensive sectors, which includes oil refineries, power stations and heavy manufacturing.

CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme (CRC) is a mandatory scheme for large businesses in the UK which do not qualify for the EU ETS. It is intended as an emissions trading scheme whereby operators must purchase allowances commensurate with their level of emissions. However, since there is no emissions cap or trading of allowances, the mandatory purchase of allowances effectively operates as a tax on emissions.

In addition to reporting requirements under the CRC and EU ETS, companies that are listed on a major stock exchange are obliged to include information on their emissions and environmental impacts as part of their annual financial reporting under the Companies Act 2006.

EU ETS MARKET REFORM

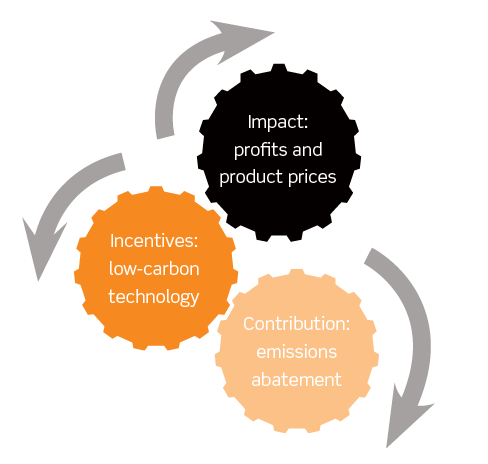

There is one very visible problem with the EU ETS – the ineffective price of carbon. However, the low price is a symptom of the wider structural issues with this market. It is important to remember this scheme is a market that the EU created with policy, and it is meant to function by implementing three main aims:

Due to its failure, the European Commission has considered the following six different proposals for market reform:

- increasing the EU reduction target to 30% in 2020;

- permanently retiring a number of allowances in phase 3;

- early revision of the annual linear reduction factor;

- extension of the scope of the EU ETS to other sectors;

- further limit access to international credits; and

- a market stability reserve (MSR).

After a very long period of consultation, in January the Commission chose to bring forward only one of the above options in its recommendation to parliament, which was for an MSR. The Commission has since been conducting technical meetings on how this proposal might best be structured. Simultaneously, EU member states have been discussing the reform at meetings of environment ministers and permanent representatives.

The MSR, in the form described below, is intended to take scarcity of supply from the future and use it to create the scarcity that is currently lacking. There are estimates that the price of carbon will increase where this MSR is used, and these figures range from prices around €18-20 per allowance by 2024 and to €50-70 by 2030. However, the changes to the carbon price will greatly depend on the form of MSR that is actually used, as well as actions taken regarding the temporarily back-loaded allowances, and whether the mechanism for free allocation of credits for ‘carbon leakage’ is tightened.

Here are the basics of the MSR as currently proposed:

- It is to be implemented in the upcoming phase 4 (from 1 January 2021), if not earlier.

- It has pre-defined rules, leaving the Commission and EU member states with less discretion over the way in which it is implemented, except for the periodic review that is to take place every four years.

- There are two key figures operating as a ceiling and a floor for the reserve in regards to the number of allowances in circulation.

- Where auctioned allowances create a surplus of over 833 million allowances, then the overage will be removed and placed in the reserve (floor to combat surplus).

- Where the surplus is below 400 million allowances, the deficit will be returned to the market (implicit ceiling to prevent too much scarcity).

- The 400 million vs 833 million figures were obtained from the Commission’s estimates on the level of spare allowances required by the power sector to cover the future sale of electricity to its customers (forward hedging).

The ‘carbon leakage’ debate is hitting a boiling point with positive indications that a MSR will be adopted. ‘Carbon leakage’ is a concept to describe the competitive disadvantage of EU companies that fall under heavier regulation than non-EU companies. Since the inception of the EU ETS, companies in the heavy industry sector (such as cement and steel) have received free allocations of emissions allowances, instead of having to purchase them at auction. One of the core issues around the lack of an effective price of carbon resides in whether or not the mechanism to measure and allocate free allowances is correct.

There is strong economic data to suggest the need to change the mechanism used for free allocation to make it responsive to economic changes in supply and demand. There is also evidence that some of these companies have received windfalls from unneeded credits by passing on the value/costs of the credits to end users, and then selling unneeded credits (for which they have been paid) on the market. In May, the Commission proposed that the current free allocation programme should remain in place and unchanged up to 2019. However, due to a senior Green member lodging an objection, European law makers are voting at the end of September on whether this proposal should go forward.

There is a new proposal to create a market reserve type mechanism for free allocation to combat carbon leakage, which could be connected to or integrated with the MSR. Global chemical company BASF has, along with other heavy industry representatives with the support of Poland, proposed a ‘Dynamic Industrial Fund’ structure to address allocation of free credits. It would function similarly to the MSR and could have potentially similar positive attributes. The political impact could be to reduce the vast divide between pro-reform supporters and energy intensive industries that are concerned about future scarcity and competitive disadvantages due to the rising energy costs in the EU.

For the power sector, market stability is the biggest concern due to the need to hedge future prices. Energy sector actors estimate that it will take at least seven years to significantly reduce the surplus using the currently proposed MSR.

As to the likelihood of the MSR being adopted, the political climate around passing reform using the proposed MSR is more positive than other initiatives in the past, due to closer member state involvement and the changes that occurred following last summer’s elections. Some media outlets are reporting that the incoming president of the EU, Latvia, has vowed support for the MSR, but this is not certain.

CRC FROM SIMPLIFICATION TO ENFORCEMENT

The CRC phase 2 qualification period has ended, and we are in the monitoring period for the first year of the phase. The Environment Agency is now more intensely pursuing enforcement against large operations that were not registered by the deadline that has just passed by using data from power suppliers obtained from half-hourly settled meters.

Now with the recession easing, companies are starting to reorganise, merge and divest. Due to these activities, some companies have unknowingly been brought under phase 2 of the scheme. One of the most common challenges for clients in regards to CRC is remembering to consider it as an ongoing concern when corporate structure changes are implemented.

Before responding to an enforcement inquiry, it is very important to assess if you have received any economic benefit from a failure to comply, which is a strong consideration of the Environment Agency (EA) when assessing civil penalties. It is also prudent to do a full analysis of whether the enforcement inquiry is correct and that your organisation has in fact triggered the qualification criteria.

Notably, meter information for recently reorganised companies as provided from a power company to the EA can be wrong and meters are sometimes incorrectly assigned to operations. Obviously, the EA will not be able to identify all failures to comply by this means, and if a compliance trigger for phase 2 has been missed there is still time to mitigate any failures to comply before economic benefits from a compliance failure will be reaped. If, however, a company misses the deadline to buy and surrender emission allowances, civil penalties can be severe.

With the enhanced enforcement of the scheme and the joint and several liability of a group of companies with a common corporate structure, it may be important to consider putting in place a CRC agreement allocating costs, losses and providing indemnities. This is of special importance where a corporate reorganisation or acquisition is to occur and CRC liability created or assumed.

ESOS: THE NEW SCHEME IN TOWN

The ESOS came into effect earlier this year. This scheme has been put in place in the UK to implement Article 8 of the EU Energy Efficiency Directive. The deadline for determining whether UK operations are caught by ESOS is 31 December 2014, and there is only a year thereafter to implement the scheme for a compliance deadline of 5 December 2015. It is generally modelled after the notoriously complex CRC scheme but with very distinct differences. ESOS will apply across sectors such as transport, property management, as well as financial and legal services, some of which have yet to be impacted by emissions scheme regulations. It is estimated that over 10,000 organisations will be impacted in the UK alone. It is generally a monitoring and reporting scheme and has no requirement to pay for emissions at this time.

Preliminary guidance has been published by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) and is nearly 100 pages in length. The EA is set to release their guidance by the end of autumn, but has said that it will not greatly elaborate on the DECC guidance, which leaves a number of key aspects unclear.

Broadly, the qualification criterion covers an ‘undertaking’ (aka a company) that has:

- at least 250 employees; or

- an annual turnover in excess of €50 million (~£42.5m) and an annual balance sheet total exceeding €43m (~£36.5m); or

- is part of a corporate group (as defined under the Companies Act 2006) which includes an undertaking which meets one of the above criteria.

The first hurdle some companies face with the scheme is the use of the concept of ‘employee’ as a threshold for compliance, which is defined using s230(1) of the Employment Rights Act 1996. Establishing whether someone is an ‘employee’ under the Act definition is not always straightforward. There is no clear line drawn between a ‘subcontractor’ and an ‘employee’ in the Act itself because case law is used to create this standard using a number of various test established by courts.

The guidance from DECC appears to be a moving target in regards to interpreting the employment standard. Originally, in a footnote, it provided that in addition to the Act standard, persons ‘engaged in the business of the organisation such as owner-managers and partners’ should also be counted in assessing whether the 250 threshold has been passed. Without any notice, the guidance has been changed to state that ‘employees’ also includes:

‘… all contracted staff, owner managers and partners employed directly by the undertaking in the UK or abroad. Companies do not have to include employees of subsidiaries or other group undertakings’.

If a group undertaking is caught by ESOS, it will need to audit energy consumed and supplied. Energy supplied is energy supplied by a supplier and generated by the participant (except from capture of surplus heat). Energy consumed includes that consumed by the participant’s assets (eg fuel consumption from fleet) as well as by the participant’s activities. Also, the data obtained needs to be verified, or a test established to explain information provided where verifiable data cannot be obtained.

Overall, the implementation of ESOS is slightly more flexible than the CRC, especially in regards to disaggregation of unrelated business within a corporate group so that they can comply separately, avoiding the need to co-ordinate. Disaggregation can be done by written agreement with the highest UK parent.

Another nuance of ESOS is automatic disaggregation, which occurs in a corporate group where there is an overseas parent with two or more separate subsidiary groups in the UK that have no corporate connection except through the overseas parent. However, the size of the separate UK subsidiary groups in their own right will not impact whether or not they need to comply. This is because qualification is triggered at the group level and is unrelated to disaggregation. The impact being that a corporate group cannot disaggregate to avoid compliance.

The various options provided for the ‘route to compliance’ will require consensus gathering initiatives and high levels of ongoing co-ordination among the various companies participating together. It is for this reason that disaggregation will probably be very common place and is an important first step in a compliance strategy, unless working as a larger group will be more cost effective.

One key feature of ESOS is that a ‘director’ has to be ‘responsible’ for representing to the EA that compliance obligations have been met. The fact that there are civil penalties attached to a failure to comply and a name-and-shame right provided to the EA, means that the importance of compliance is likely to be recognised at a board level.

POTENTIAL FUTURE TRENDS

One heavily debated aspect of ESOS and the EU directive has been the level of energy use information to be submitted to the enforcing agency, and aspects of the information that would be disclosed to the public to incentivise energy efficiency activities. DECC even had a special consultation on the question of public disclosure, but in the end this was decided against. Having much of the information in ESOS publically disclosed would be an enormous competition issue for many operations caught by the scheme, but the disclosure debate has some substantial support at the EU level and is something to watch.

While at an EU level, fixing the EU ETS using a MSR is a primary focus, if the current political direction remains the same once the market is reformed, it is not entirely implausible that ESOS could be used as a pre-compliance measure to prepare new sectors for an expanded cap and trade scheme.

It is clear that creating incentives for emissions reduction through energy efficiency is a priority for the UK and in the EU. Proactive planning from a corporate compliance perspective will be vital to manage the ever increasing costs.