There is a long-established truism among white-collar crime lawyers that when a country goes into a recession, financial crime rises to the surface. And with various reports suggesting Brexit uncertainty and low business confidence could tip the UK economy into a downturn, those specialists are predicting more work will hit desks soon.

‘Downturns will often reveal wrongdoing in accounting treatments as the tide goes out and you’re going to see who’s looking embarrassed,’ notes Jonathan Pickworth, head of white-collar crime at White & Case.

Corporate crime specialists are reporting a healthy pipeline of defence work, with money laundering and bribery, accounting and tax fraud key enforcement areas for the likes of the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), the National Crime Agency (NCA) and HMRC. The NCA is making its presence felt through new powers under the Criminal Finances Act 2017 for issuing unexplained wealth orders, with several more having taken place since Zamira Hajiyeva, the wife of an Azerbaijani ex-state banker, was revealed this summer to have spent £16m in Harrods over a decade.

Meanwhile, Patisserie Valerie is under investigation by the SFO following the unmasking of a reported £94m accounting hole in 2018. The case has sparked more scrutiny over the quality of auditors’ reviewing procedures and saw the Financial Reporting Council investigate Grant Thornton over its auditing of Patisserie Valerie last year.

At the start of the year, however, there may have been dampened spirits at the SFO after it dropped its investigations into pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and engineering company Rolls-Royce over weak evidence. The move came just a few months after the SFO’s accounting fraud case against two former Tesco directors collapsed at trial.

Nevertheless, fresh cases have taken centre stage at the SFO under the leadership of director Lisa Osofsky, who was appointed to the post last August following Sir David Green’s six-year tenure. She has since made various pledges to fight corporate crime, including speeding up investigations and more collaboration with cross-border and UK enforcement bodies. The National Economic Crime Centre was set up by the Home Office last October to help co-ordinate enforcement agencies in the UK.

Out with the old

The SFO’s decision to drop its cases into Rolls-Royce and GSK has had its critics. ‘A lot of people were surprised by the decision,’ says Norton Rose Fulbright disputes partner Pamela Reddy.

But others see a pragmatic strategy from the SFO to cut short legacy work to prioritise fresh cases. ‘There’s been some negative media reports around dropping cases, but that makes perfect sense if the cases weren’t strong enough to take forward,’ says Brown Rudnick partner Anupreet Amole.

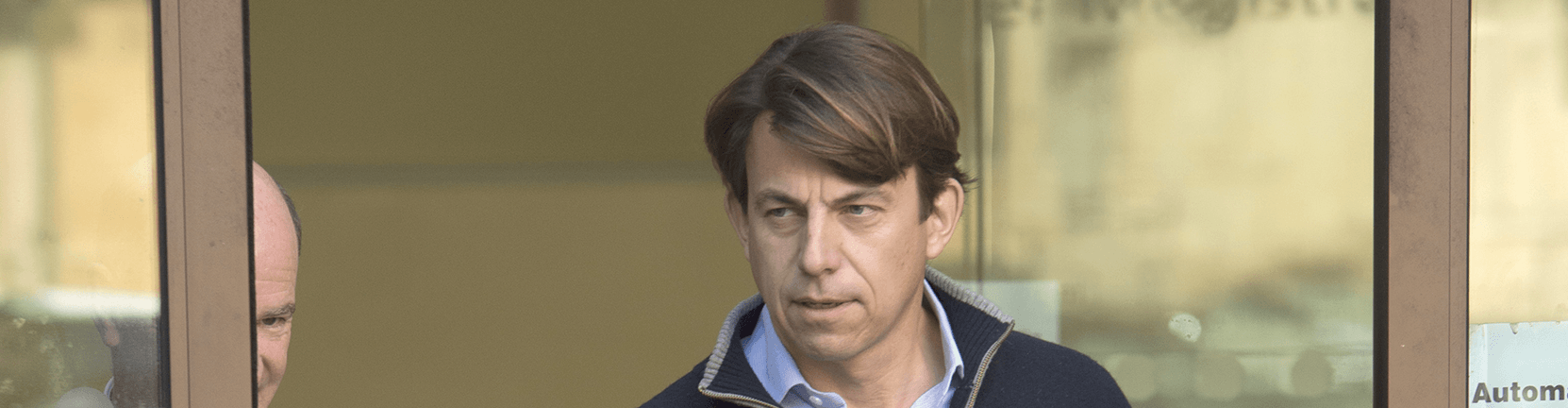

‘The prospect of getting evidence out of China was zero [in the GSK case]. It has taken up a lot of resources,’ adds Richard Kovalevsky QC, head of financial crime at disputes specialist Stewarts. Kovalevsky and Louise Hodges, head of Kingsley Napley’s white-collar crime practice, report a recent uptick in SFO activity in investigations, despite some settling-in time for Osofsky.

However, some practitioners are less impressed. ‘As an observer of the SFO, things have seemed quiet over the last 12 months – a number of big cases have been dropped, leaving a big gap to fill,’ says Pickworth. ‘There have been fewer things announced, let’s put it like that,’ remarks David Savage, a financial crime partner and Kovalevsky’s colleague at Stewarts.

Osofsky has put emphasis on the role the private sector can play in helping to fight corporate crime, with lawyers noting changes in the regime since Green departed. ‘She has made it clear that she’s reasonably happy for companies to do some level of their own investigation before deciding to self-report, whereas David Green would have said that was trampling the flowers of the SFO’s investigation by getting the first accounts from the witnesses,’ says Pickworth.

In-house counsel have largely welcomed the shift in stance. Says Denis Rice, assistant general counsel for crime litigation and prevention at Royal Mail: ‘It is fair and balanced for the SFO to let companies look at the issue first themselves. It would be foolhardy to report something you’ve not investigated yourself and the company needs to be able to understand the extent to which it has stepped over the line.’

Nonetheless, recent unsuccessful investigations and perceived SFO inactivity by some has not convinced everybody that it is the private sector that needs to be more proactive. ‘Osofsky wants to encourage companies to self-report, but it’s a bit lazy. They’ve had a real drop in investigations, but she’ll say that she’s not as well-armed with tools as they are in the States,’ notes Reddy.

Where the SFO appears to have made more of a mark is in a much-cited interview Osofsky gave to the Evening Standard in April, in which she advocated the use of more covert surveillance techniques in investigations. The article has sparked speculation that Osofsky – a former GC of the FBI – may adopt investigation tactics more commonly deployed in the US, such as encouraging suspects to turn informant by wearing a wire. But the SFO has not stated any change in policy: it can deploy covert investigative techniques, but encouraging suspects to wear a wire is far from standard practice.

White-collar crime partners seem unsure whether US-style measures could be feasibly implemented in the UK: ‘My experience is that English juries tend to be very sceptical of that type of evidence. We don’t have a history of co-operating with witnesses like they do in the US,’ says Timothy Bowden, a white-collar crime partner at Dechert. ‘Historically, corporate fraud cases have been whistleblower or self-report cases, with covert surveillance more suited for real-time detection. It is a technique used in live investigations conducted by the NCA and HMRC, rather than the SFO,’ adds Hodges.

In with the new

In August, the SFO issued a five-page guidance document outlining to companies what they should expect if they report suspected misconduct and clarifying that co-operation will be a ‘relevant consideration’ in deciding penalties. Dechert criminal defence partner Caroline Black says clients feel reassured by formal guidance outlining how to approach self-reporting. ‘There’s scope for companies to enter into DPAs [deferred prosecution agreements] – they just need to be alive to the corporate guidance. It sets out a clearer guide for companies, although it has been informed largely by public thrashing,’ adds Amole.

But Savage calls the guidance ‘disappointing’ for clients in so far as it confirms that even full co-operation will not guarantee that a company will receive a particular outcome, including securing a DPA. A DPA is a contractual agreement between a prosecutor and an organisation, where the corporate has admitted to misconduct but has criminal proceedings suspended under certain terms, such as co-operation in a wider investigation or paying a fine. They are often touted as preferable to costly and lengthy trials for companies, and partners are unanimously in agreement that more are on their way.

self-report.” Barry Vitou, Greenberg Traurig

‘When you think of the big scandals in the past, it’s usually where a company has not had a culture of doing the right thing, so if DPAs can encourage openness and transparency, it’s probably a good thing,’ notes Mark Maurice-Jones, Nestlé’s UK and Ireland GC.

However, few lawyers dispute that progress has been slow in pushing DPAs through the courts since they were introduced under the 2013 Crime and Courts Act. Serco Geografix made up the ‘famous five’ club of companies signing up to DPAs in July, following Standard Bank, Sarclad, Tesco and Rolls-Royce (see box, below). Moreover, Pickworth says recent DPAs have shown themselves to be problematic and that, despite the SFO’s efforts to encourage self-reporting, it is far from a no-brainer for companies to be compliant.

‘You end up with a resolution for the company of sorts, but that’s not the end of it. As part of the terms of the DPA, the company has to not only pay the penalty but also agree to co-operate with the SFO until the relevant individuals are held to account, which could be years,’ he says. Barry Vitou, head of Greenberg Traurig’s London white-collar and investigations practice, picks up the point: ‘DPAs are effective in that they draw a line under criminal investigation, but on their own I don’t think they are enough of an incentive for companies to self-report. There is a complex calculus, which a corporate will consider before deciding what to do.’ Pickworth adds that the way in which alleged offenders have fared in the UK courts shows that there is some debate to be had: should the SFO wait to resolve matters with a company until after criminal proceedings against individuals are settled?

So far, DPA fines have been high for giants like Tesco and Rolls-Royce. Tesco’s DPA in 2017 cost it a £129m fine and £3m in investigation costs, but a year later its directors were acquitted at trial. The same year, Rolls-Royce entered into a £497m DPA but had its investigation dropped by the SFO in February. Harry Travers, a business crime partner at BCL Solicitors, ponders: ‘Is it right for the state to extort large financial penalties from companies in respect of the conduct of individuals who are ultimately found not to be guilty?’

When DPAs were introduced, Parliament considered whether the agreements could also apply to individuals, but proposals did not take off. However, in the light of difficulties enforcement agencies have experienced in getting cases to trial, Pickworth suggests it may be time for a rethink: ‘You’re rolling the dice if you go to trial. You can see a circumstance where if there were provision for DPAs for individuals, you could have everybody in the room all at once, including the company, and agree to all the relevant facts that would justify a DPA. It’s very difficult for the SFO to get its cases all the way through to trial and to a successful conclusion, so DPAs for individuals might resolve some of those issues.’

Kovalevsky is unsure, however: ‘Our judicial system has a long way to go before it accepts it. Public opinion is against it because people want to see executives bought to book.’

With more DPAs expected, the spotlight will be on the SFO and its pledge to speed up investigations and achieve results. For now, the jury is still out on DPAs as to how effective they are at encouraging companies to self-report.

Anna Cole-Bailey

The ‘Famous Five’ – a history of DPAs

Serco Geografix, 2019

Serco’s deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) was approved in July this year after the outsourcing company admitted to misleading the Ministry of Justice by understating its profits between 2010 and 2013 over electronic monitoring contracts it held with the Government. Serco was ordered to pay a £19m financial penalty and nearly £4m in investigation costs, with the Serious Fraud Office (SFO)’s investigation having run for six years.

The DPA will run for three years, over which time Serco must co-operate with the SFO and other law enforcement authorities, and report yearly on the effectiveness of its ethics and compliance programme. Big Four accounting firm Deloitte was also fined £4.2m by the accounting watchdog for its audit of Serco.

Tesco, 2017

Following a high-profile investigation, Tesco entered into its DPA with the SFO after the regulator determined that ‘a culture existed at Tesco that encouraged illegal practices to meet accounting targets’ between February and September of 2014.

Tesco referred itself to enforcement authorities after discovering issues in its financial statements and reported that revenues had been incorrectly recorded as profit. Former directors Carl Rogberg, John Scouler and Chris Bush were charged over allegations of fraud and false accounting in 2016, although their cases collapsed at trial in 2018. Tesco agreed to pay a £129m fine and £3m investigation costs.

Rolls-Royce, 2017

Sir Brian Leveson approved the Rolls-Royce DPA following a four-year bribery investigation by the SFO. The iconic engineering company took responsibility for criminal conduct spanning three decades in seven jurisdictions: Indonesia, Thailand, India, Russia, Nigeria, China and Malaysia. The firm paid £671m to settle corruption cases with UK and US authorities.

Sarclad, 2016

Manufacturing company Sarclad agreed a DPA with the SFO in 2016 after a three-year bribery and corruption investigation by the agency into commercial contracts secured by Sarclad.

Three company executives were charged with conspiracy to corrupt and conspiracy to bribe but were acquitted in July this year. The firm accepted the charges of failure to prevent bribery in relation to the systematic use of bribes to secure contracts for the company between 2004 and 2012, and paid £6m in its bargaining plea. The contracts had a total value of over £17m.

Standard Bank, 2015

The now-expired deal between Standard Bank and the SFO, which came to an end in 2018, was the first DPA to be struck in the UK and the first under section 7 of the Bribery Act 2010.

The charge related to a $6m payment sent to Standard Bank by a former sister company in 2013 and on to a partner in Tanzania, which the SFO alleged was to bribe members of the Tanzania government.

Standard Bank paid nearly $26m in penalties and was ordered to pay Tanzania $6m in compensation, as well as £330,000 in SFO investigation costs. Under the DPA terms, the bank was required to commission an external consultant to report on its anti-bribery and corruption controls and procedures.