‘We are on the threshold of what is going to be the biggest restructuring challenge in the history of insolvency. Nothing will have come close’. So says Mark Phillips QC of South Square Chambers on the Corporate Governance and Insolvency Act 2020, passed in June 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 crisis. The legislation’s stated purpose is to give companies affected by the lockdown and the potential fallout from the UK’s exit deal – or lack of one – with the European Union the breathing space and tools needed to survive a mounting debt or liquidity crisis.

The reforms to the insolvency and company regime introduced by the act are a short-term debtor-in-possession moratorium procedure; the suspension of termination on insolvency in supply contracts; and, perhaps the most groundbreaking, the introduction of a cross-class cramdown that allows one class of creditors to agree to a restructuring plan with the court which others may not agree to. But just how revolutionary is the legislation? Will it prove to be a truly effective tool for keeping for troubled businesses afloat or merely a stay of execution?

Phillips QC is extremely positive about the new provisions and how useful they will be in preventing the wave of insolvencies that many analysts are predicting to happen when government support schemes end. ‘The moratorium procedure gives companies the ability to restructure themselves while the directors stay in possession while the new restructuring and arrangement provisions take us from CVAs and schemes of arrangement towards a new form of arrangement where not every class of creditor needs to consent,’ he says. ‘This gives companies massive flexibility in dealing with their debt problems’.

Stressing the revolutionary nature of the new provisions, he also strongly advises in-house counsel to get clued up as to what they entail; as they are more than likely going to have to get to grips with them soon. ‘There is virtually no business in this country that will avoid being exposed to the new provisions, either for themselves or because they are involved in a sector or a supply chain where others are’.

James Roome, an Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld restructuring specialist, says ‘the act is a much more significant departure as a matter of English law than some people appreciate’, and singles out the suspension of termination on insolvency supply contracts as a particularly useful measure for assisting companies in conserving the value as a going concern. ‘The ipso facto protection, where certain suppliers will not be able to terminate their supply contracts based on the granting of a moratorium or the making of administration orders is very helpful and something that will undoubtedly help companies.’

Nick Angel, Milbank

However, the legislation is no silver bullet to solving the UK’s impending insolvency crisis. Roome also believes the pre-existing legal provisions were sufficient to cover the majority of restructurings: ‘Since the dramatic increase in going-concern debt restructurings that happened in the early 2000s, English law has emerged as a tool that has allowed a huge number of consensual restructurings to be achieved for large and multijurisdictional companies.’

Similarly, Blair Nimmo, partner and UK head of restructuring at KPMG, is cautious when appraising the effectiveness of the cross-class cramdown. ‘While for large businesses in certain sectors with certain financial structures it will be incredibly helpful, I don’t think you’ll find lots of cases where it is applicable’. One of the issues, in his opinion, is that it will take time for practitioners to feel comfortable in using the new tools. ‘1986 was the last time that insolvency law was changed in such a groundbreaking way, and if you look back it took many years for CVAs to be used in large numbers. As yet we have not seen the provisions used in large numbers at all’.

Call in the specialists

Whatever the success the Corporate Governance and Insolvency Act 2020 has in safeguarding British business at a macro level, it is important for in-house counsel to get their heads around it and the tools it provides them to get ahead of any problems further down the line. As Kyle Williams, managing director of EMEA corporate, finance and consumer banking legal at Goldman Sachs International says, the world of insolvency and restructuring is usually one of highly skilled, but rare, practitioners. ‘Out of a 600-person law firm, you might have eight people doing high-level restructuring, and when I was based in New York there were a handful of really top-level restructuring practitioners. As an in-house lawyer, on the other hand, you want to be someone who can cover all the bases legally speaking. This means that in-house lawyers often don’t have experience of this area.’

As such, getting expert advice is critical, as the process of a corporate restructuring or scheme of arrangement can contain potential pitfalls for those lacking experience. Nick Angel, partner and co-head of Milbank’s restructuring practice, stresses the added benefit that a top-notch adviser can bring. ‘I would very much encourage in-house legal advisers to reach out for specialist help. If you’re a director of a company, and this is a new experience for you it can be terrifying. Restructuring advisers spend their whole careers dealing with crises, so we tend to be a pretty calming influence and we’ve seen it all before. It is useful to be able to turn to somebody who has done this before and can tell you whether or not you are in trouble’.

Philip Hertz, global head of restructuring and insolvency at Clifford Chance adds that the act itself of seeking specialist help adds another safeguard. ‘You really need to understand the problem, and to do that you must to get good advice, because directors rarely get criticised after the fact if they have proactively sought appropriate financial and legal advice. If they have made efforts to seek advice but the worst still happens, it is hard to criticise directors – as long as, of course, they have not simply ignored that advice’.

Jacquie Ingram, Milbank

The other truism of the insolvency and restructuring world is ‘a stitch in time saves nine’: things can get unmanageable very quickly if proper action is not taken when there are warning signs. Jacqueline Ingram, a partner in Milbank’s European financial restructuring group, emphasises how critical this is. ‘The number one piece of advice I could give would be this: the earlier you acknowledge the situation and start planning, the better you’ll come out of it. Companies who put their head in the sand run the risk of coming up against a liquidity wall. When that happens, things become very difficult and there are a real lack of options’.

It is also key to remember that there are significant steps that can be taken before the company is out of its depth and really struggling. ‘There are tools available for companies to use before they are right on the brink’, Ingram continues. ‘A scheme and even a restructuring plan can probably be done for a company that’s not insolvent’.

Ken Baird, Freshfield Bruckhaus Deringer partner and head of its global restructuring and insolvency practice, recommends that in-house counsel are proactive and willing to trust their instincts. ‘Often in-house counsel might be nervous about advising management to seek specialist advice about an impending liquidity issue and then being rebuffed when they do so. I would advise them to push the issue. Whatever time you think you’ve got to undergo a restructuring, double it. The whole process of beginning and formalising engagement with stakeholders, beginning and concluding a discussion and then executing the outcome of the discussion takes more time than you think’.

There are some basic measures to buy time that Baird says in-house counsel or other advisers often miss. ‘One example is the fact that facilities typically run on interest periods of one, three or six months. If you switch your interest periods from one month to six months, you just bought yourself five months of not having to make a representation. Plan early and think ahead, and you can buy time in the process’.

Do it now

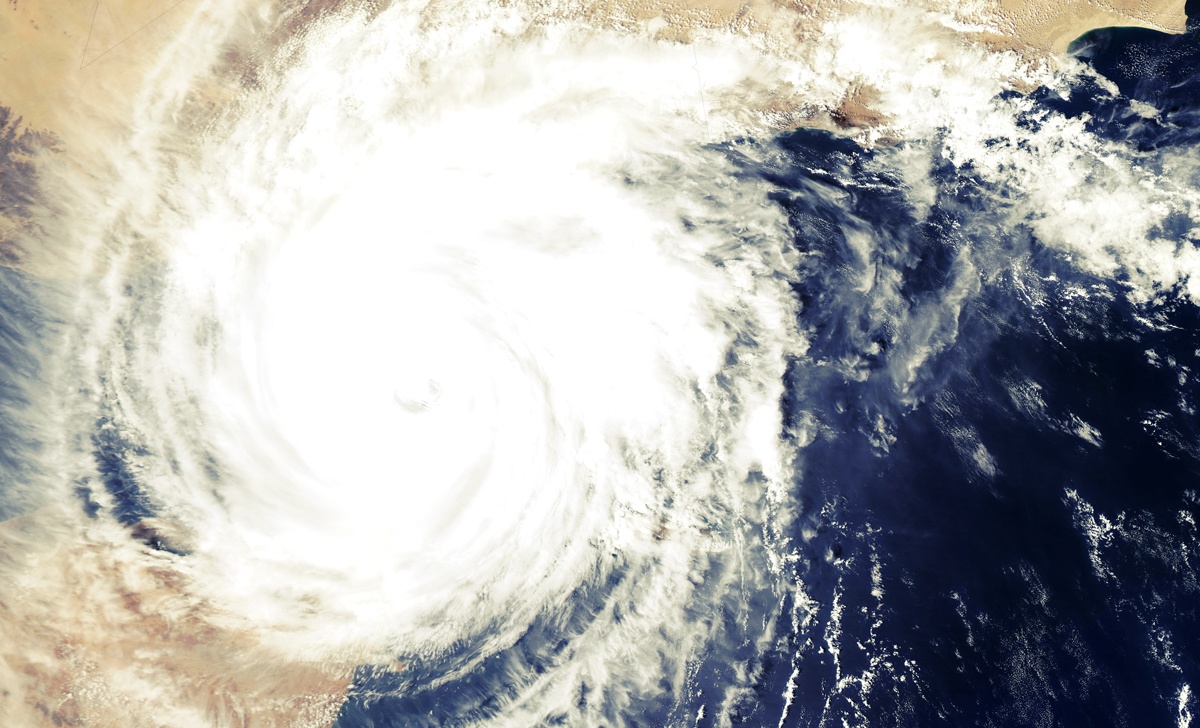

The UK moves into 2021 with an unprecedented level of uncertainty looming over its business world. The twin shocks of the end of government coronavirus relief measures and a potentially disruptive European Union exit arrangement have led many analysts to predict dark times ahead for UK Plc starting in Q1 of 2021. There is a feeling that British business is currently in the eye of the storm. ‘We haven’t seen a significant wave of insolvency proceedings, but we have seen a large spike in schemes and restructuring plans, especially beginning in August,’ says Ingram. ‘As the furlough scheme ends and some other government support programmes roll off, we might start to see more insolvency proceedings, particularly in the retail sector around Christmas, which is always a crucial time for them.’

Ken Baird, Freshfield Bruckhaus Deringer

Hertz also emphasises the uncertainty of the future economic picture: ‘We are still unclear if we are in a U, V, Nike Tick or L-shaped recovery curve, and of course this will differ depending upon the industry and sector. This is hard for in-house counsel or directors to mitigate against.’

Despite this, Phillips QC advises that it would be a mistake for corporate advisers to not take action now to safeguard the future of their business, and urges them to do their bit for the economy as a whole by utilising the breathing space they now have. ‘What I would say to in-house lawyers directly is that this is real for absolutely every company, and lawyers need to understand the mechanics of the new insolvency and restructuring rules and forget about the stigma of restructuring. Everyone is in the same boat, and this wasn’t caused by bad management, it was caused by a virus. Thanks to the new Bill, we will have every positive aspect of the American chapter 11 proceedings available to UK insolvency procedure, so use this time wisely. We’ve now got a window until the 31 December’.

Angel agrees, ending on a positive note for anyone feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of managing a scheme or restructuring over the next few months. ‘The main takeaways for a GC are these: Don’t panic, plan early and make sure you’re talking to somebody who does this for a living. The other thing to bear in mind is that you should be driven by good commercial common sense. Most of what we deal with, like directors’ duties and wrongful trading, sound intimidatingly complex, but responding correctly is actually quite intuitive as long as you have good commercial judgement.’