Legal spend is the second-largest ‘cost centre’ for £21bn global banking giant Barclays. This tantalising statement is in the bank’s 2018 Request for Quotation document, sent to law firms ahead of its final panel review this year and seen by The In-House Lawyer. The document provides detail on what Barclays describes as this ‘sizeable’ legal spend.

In the 18 months to January this year, for instance, around 35% of its legal budget was spent internally in running an in-house legal department that dwarfs many major law firms at more than 750 staff. The rest was spent externally, about half in the Americas and just over a third in the UK.

To give context, Barclays chief of staff to the group general counsel Alison Gaskins recently told a room of leading GCs that the bank has managed to bring down legal costs by a ‘significant amount’ in recent years. Savings generated are believed to run into the tens of millions of pounds.

This culminated in July with the completion of its final global panel review, ahead of a long-planned phasing out of formal reviews by 2021. As recently as 2012, Barclays had more than 1,000 external advisers globally, but that has shrunk to around 100 today. The new model is touted as replacing resource-intensive adviser reviews with an ongoing relationship management system and, over the years, has seen initiatives ranging from value account systems to what are dubbed ‘effective fee arrangements’ (EFAs) introduced.

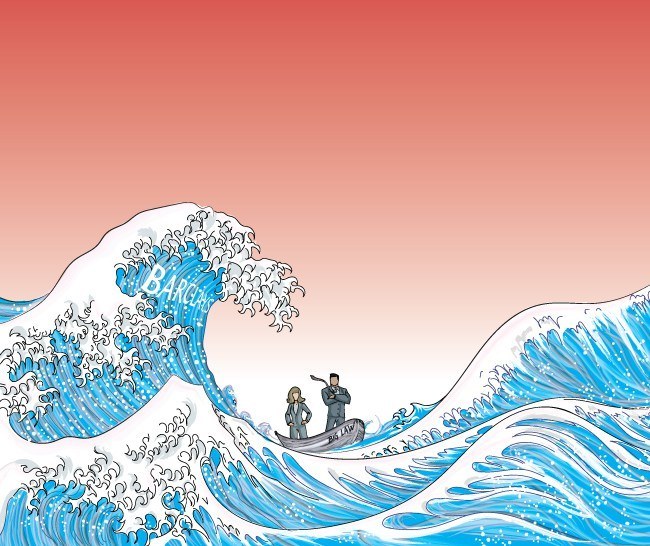

However, some private practice partners question the merits of having such institutional relationships post-Lehman. Given the rise in popularity of private equity work, they question whether Barclays still has the clout to dictate terms to the most successful law firms.

One City partner at a panel firm describes the tension: ‘Law firms and their managers are very keen to say they act for banks, but if you look at the behaviour of their top partners, they want to act for sponsors that pay more.’

A two-year pilot of the new model Barclays launched with its top 30 firms saw just 20% embrace what the bank wanted, Barclays head of external engagement Stéphanie Hamon concedes. The question then is whether the bank can force dozens of major law firms to adopt a radical overhaul of their working arrangements at a time when more advisers are shifting resources away from banking clients, particularly commoditised volume work.

One panel firm partner is optimistic: ‘Barclays will become a much more interesting client for everyone – it will be all about value. It’s an interesting challenge. The firms that are willing to be more creative will be able to make better margins. There is enough appetite out there for this not to be a huge gamble.’

Hamon is unsurprisingly bullish about Barclays’ brand and buying power: ‘We are very confident. Maybe you’ll quote this back to me three years from now but we didn’t think we’d be at the stage we’re at now. Change has happened quicker than we thought.’

Function of the future

Changes to its legal function have been shaped by the environment that Barclays has faced in the last decade, dominated by turbulence, controversies and shifts in strategy. In March this year, it agreed a $2bn settlement with the US Department of Justice following an investigation into allegedly fraudulent mortgages sold between 2005 and 2007. It has also been fined more than $2.4bn for manipulating the forex market.

The most high-profile issue, however, has been the ongoing Serious Fraud Office (SFO) investigation into its £12bn fundraising from Qatar at the height of the financial crisis. Charges of conspiracy to commit fraud against the bank and four former directors were filed in June 2017, only to be dismissed less than a year later. The SFO has since applied to reinstate them.

Research published by Thomson Reuters earlier this year showed the UK’s four largest banks had set aside £14.6bn during 2016 to tackle litigation and regulatory investigation expenses – more than half of the FTSE 100’s litigation costs. Many expected there would be a few years of upheaval at banks post Lehman before a return to business as usual. A decade on, however, and the regulatory environment is only getting more stringent. Ring-fencing reforms, for instance, saw Barclays in March 2016 split into two divisions: Barclays UK and Barclays International.

In early 2013, group GC Mark Harding announced he would retire after ten years. One of Europe’s most high-profile GCs, Harding and former global GC for corporate and investment banking, Judith Shepherd, were reportedly part of a group of executives interviewed under caution by the SFO in its Qatar investigation. Harding’s replacement, Bob Hoyt, was seen as a surprise pick for one of the most senior legal roles in banking. There had been months of speculation that it was a two-horse race between then deputy GC Michael Shaw and Shepherd.

The well-regarded Hoyt joined from PNC Financial Services Group and sits on the bank’s executive committee. Previous public service roles include GC at the US Department of the Treasury and special assistant and associate counsel at the White House. Such credentials were widely seen as reflecting concerns that the bank would be facing a robust US enforcement environment for the foreseeable future.

A string of senior lawyer exits were to follow from early 2015. Shepherd left; Shaw joined The Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) as GC less than a year later; EMEA GC Erica Handling left for BlackRock; global head of financial crime Jonathan Peddie went to Baker McKenzie; and global head of legal for corporate banking Joanna Carver joined Lloyds Banking Group. Investigations and enforcement head for Europe and the Middle East Jake McQuitty also left for private practice.

However, Barclays’ legal department has grown at the same time. The team is split now between about 470 in the UK, 170 in the US and the remainder elsewhere. In the past three years, the emphasis has been on operational management of the legal team. The first 18 months were about setting up systems to record data, from which it has looked to bring costs down. Gaskins and Hamon work alongside head of business management Jon Doyle on the operations push, and are touted as leading figures in the emerging community of business services professionals working with in-house legal teams. Hamon led the team that worked over the past two years to develop Barclays’ new framework for more active, ongoing management of external counsel.

Barclays key advisers

- Addleshaw Goddard

- Allen & Overy

- Ashurst

- Baker McKenzie

- Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft

- Clifford Chance

- Dentons

- Eversheds Sutherland

- Hogan Lovells

- Linklaters

- Norton Rose Fulbright

- Pinsent Masons

- Simmons & Simmons

- Slaughter and May

- Stephenson Harwood

- Taylor Wessing

- White & Case

- Willkie Farr & Gallagher

‘Time and experience has shown that where Barclays go, other in-house teams follow,’ says one consultant.

You don’t have all the answers

At its panel launch event in July, Hoyt talked a lot about transparency and collaboration. Firms, however, wanted to hear about what not having a formal panel process meant, from which the term ‘legal professional of the future’ was brought up.

Hamon elaborates using textbook innovation rhetoric: ‘One of the attributes of the legal professional of the future is to thrive in ambiguity. In an environment that is fast moving and fast changing, you don’t have all of the answers, so it’s about being able to embrace that. You try, and if you fail, fail fast.’

Law firms were assessed against six ‘expectations’: legal advice; thought leadership; collaboration and teamwork; value for money; diversity and inclusion; technology. The latter two were added this year, with descriptions for each across two pages in the tender document. Barclays also set out four key focus areas: long-term and mutually beneficial relationships; innovation; collaboration; and reducing hourly rates in favour of EFAs.

Relationship management is vital, Hamon says, and is at various degrees of sophistication within firms. Barclays has developed a working group of panel firms to help speed up improvement in this area: ‘The firms need to be internally championing Barclays and what we’re trying to do, but conversely they need to make sure they deliver the entire firm to us.’

Hamon says Barclays wants panel firms to take the initiative, feeding back successes through meetings with each other, sharing best practice. While the in-house team has its own views on what the lawyer of the future and relationship manager should look like, Barclays wants firms to lead the debate on this.

About 45% of the bank’s external work is billed on hourly rates, but Barclays has a rough target of pushing this down to just 15-20%. To drive this, a menu of EFAs has been created as guidance, with Hamon conceding that while new pricing approaches can be ‘puzzling’ at times, the bank is open to ideas. ‘This conversation is going to happen more on a bilateral basis for obvious competition issues but it’s trying to help educate and move them on in that journey.’

In addition Barclays’ value account system, introduced in 2014, is often highlighted. It initially applied only to ‘preferred’ advisers, but has since been extended to the entire panel, and is triggered when Barclays spends more than £1m with a firm in a year. It works by allocating firms an annual value of free legal services – primarily through legal advice and secondments – they must provide in return for an agreed volume of work, with the unpopular downside being that firms must reimburse Barclays if they fail to meet those benchmarks.

Hamon says firms wanted to keep and extend the system, because panel spots on large institutions often leave them feeling they are investing more in the relationship than they get in return. With this in mind a virtual credit is created against every firm that goes above the £1m threshold, calculated as a percentage of the revenue they are generating. This credit can be used to by Barclays to fund secondees, rebates or investment in innovation.

‘When the secondment pot is empty, we can’t hound the firm for secondees anymore – that’s a way to make it proportionate to the revenue they generate.’ The upshot of this is that Barclays cannot take advantage of its position to overburden firms with demands for more resources, moving away from a Wild West scenario.

Other changes include a revision of the category system, removing ‘core specialist’ to only have ‘primary’ and ‘specialist’ firms. A three-card rate system that asked firms to price mandates according to whether they could be defined as ‘strategic’, ‘medium’ or ‘flow’ was also removed. As this system was deployed to get firms thinking about how they should be pricing mandates, the expectation now is that they will do that automatically.

There is also a diversity and inclusion working group, which is again aimed at bringing firms together to progress the agenda beyond firms simply pointing to diversity awards and annual events. Barclays also assesses every matter worked across diversity metrics, such as gender balance of the team and representation by ethnic minorities.

The bank refuses to name any of the firms on its panel, and Hamon is coy on the split between primary and specialist advisers, other than to say the primary number is ‘much smaller’. Of the 140 firms on 2016’s panel, only 15 were primary. She describes moving firms towards an employer-employee relationship, emphasising ongoing feedback, including ‘adult feedback’ when issues arise.

In practice, Barclays’ in-house team uses a law firm selector tool: each panel firm is listed and categorised so that when an in-house lawyer needs a firm for banking work in Germany, as an example, a selection of firms matching those categories are available to use. Conversely, each firm knows its ‘share of wallet’ ie, its rank in terms of how much work it is getting in different areas – without knowing which firms it is behind or ahead of. This means when a firm asks for more work in a particular practice area, Barclays legal team can ask that firm to show why – based on the capability it said it has – it should get a bigger ‘share of wallet’.

‘They can know whether there is one, two or five firms in ahead of them. We also tell them it’s not the only data point to look at, though, because their share is also proportionate to the size of their offering. We can then we have that discussion around how they can target more work.’

According to Hamon, of the 30 firms piloting the new model over the last two years, 20% were on board, 60% had the appetite to change, while the rest did not. She can see hurdles in getting the majority to convert, such as Barclays not being a firm’s biggest client (the tender document specifically asks firms to rank revenue from Barclays in global and financial services client portfolios over the last three years).

‘For some firms that are operating in certain markets they’re really successful the way they are and it’s really hard to reinvent yourself when you haven’t felt any heat from the changing market. Maybe they need a little wake-up call and haven’t had it yet.’

Lawyers as suppliers

Alongside Barclays’ refusal to name its firms, firms are prohibited from talking publicly about the panel. Every relationship partner The In-House Lawyer spoke to immediately raised this ‘punitive’ approach: ‘Barclays have made it clear we speak to you guys at our own risk,’ says one.

A number of obvious firm names have quickly filtered through, but it is harder to trace those that are ‘primary’ and those that are ‘specialist’. Allen & Overy (A&O), Clifford Chance (CC), DLA Piper, Linklaters and Simmons & Simmons have historically taken the bulk of the work. Baker McKenzie is believed to have pulled in £10m annually from Barclays in recent years. Disputes specialist Boies Schiller Flexner has handled a significant amount of US regulatory work for the bank.

But during the 2016 panel review DLA lost its multimillion pound-a-year spot, although given the nature of the work the firm was reportedly doing, Barclays was often cited as more of a trophy client than a driver of profitability for the firm. CC has also seen its role reduced over the years. The sense externally is Barclays is more interested in individual lawyers or teams within firms, rather than wider firm brands.

As such, partners talk of work moving with lateral hires. Ropes & Gray, for instance, was boosted by the hire of former CC white-collar crime partner Judith Seddon earlier this year. Similarly, Barclays former head of financial crime, Jonathan Peddie, was critical to maintaining Bakers’ Barclays relationship when he joined as partner in 2015. One panel partner says their firm had yet to receive substantial work from Barclays in a certain practice area, while potential laterals at non-panel firms had. ‘How does that work?’ they question.

Hamon often cites feedback that firms are using Barclays’ initiatives with other clients as justification for its robust procurement stance. Barclays has long been seen by firms as pushing the agenda on fee structure creativity for years, ahead of most clients. Some relationship partners concede the extra level the bank is seeking is difficult. Says one: ‘It keeps us on our toes – it is challenging traditional thinking. There is no doubt about that but you wouldn’t be on the panel if you didn’t get that.’

Another is more circumspect, particularly on whether Barclays’ complex approach is workable in practice. ‘It remains to be seen how it’s going to develop, but it will require innovative thinking and will depend on the level of buy-in from both sides.’

Selected terms from Barclays’ tender document

Broken Deal Discount

Please confirm that you will provide Barclays with at least a 50% discount on all fees for time incurred by your firm on failed or aborted deals that were originally pass-through matters, eg client payable… This is a mandatory requirement.

Most Favoured Nation

Please confirm you will provide ‘most favoured nation’ status to Barclays by offering improved commercial terms no less favourable to those agreed with other banking and financial services clients. For example, where required, Barclays would receive a reduction in rates to match those preferential rates.

Relationship Team Model

Given what you know of the expectations, Barclays’ objectives, your experiences over the current panel period and considering your proposed strategic plans, please provide a proposal on the composition of your firm’s relationship team, giving specific consideration to the following:

- diversity;

- limited size of relationship team;

- ability to drive change within your firm and champion Barclays’ position internally;

- maintaining eff ectiveness; and

- ability to deliver.

The tender document requires each firm to stipulate a minimum number of secondees it is willing to provide. Many partners say they typically send more than is required because it is an opportunity to develop the relationship. Some, however, complain about banks using secondees as a pool for hires and have reservations about Barclays’ already sizeable in-house team. In general, firms are weary of pressure from banking clients for secondees and have increasingly pushed back at heavy-handed attempts to extract free lawyers.

One panel firm partner commented: ‘In a market where there is a lot of work at the moment, these relationships have to work mutually. The market is evolving and while banks are key clients, they are not the only clients around.’

Another is more critical: ‘Banks gave up long ago any interest in picking up law firms based on quality rather than economics. Banks see lawyers as suppliers, exactly like someone selling paper for printers. A lot of the work lawyers do is like buying paper for the printers. It’s all about the price.’

We’ve set up shop

In August, Barclays’ half-year profits fell by a third to $1.7bn for the six months to 30 June, while revenue was flat at £10.9bn. About £2bn in litigation and conduct costs ate into profits, but group chief executive Jes Staley – recently hit by regulators for more than £600,000 after using internal systems to try to identify a whistleblower – was bullish following a strong second quarter.

‘It was the first quarter for some time with no significant litigation or conduct charges, restructuring costs, or other exceptional expenses that hit our profitability. In effect then, it is the first clear sight of the statutory performance of the business, which we have re-engineered over the past two and a half years.’

An optimistic take, perhaps, but Hamon says the 100 firms on the final panel will likely reduce as ‘legacy litigation issues’ fade away in coming years. Head of relationship management Christopher Grant is more direct in what influences the panel’s makeup: how well firms respond to the bank’s demands. Those that do will bloom, those who fail, will not.

‘We’re setting up shop and have been, over the last two years, really clear about what we expect to see from our firms, and the need to become all-solutions providers to everything we need.’

Hamon adds: ‘It’s fair to say there was a certain level of scepticism as to what we were trying to achieve. The firms that have done better realised it was as much in their interest as ours.’

Optimistic relationship partners say Barclays is just pushing firms to show the initiatives they have talked about for years: low-cost centres, alternative providers, technology. But others worry: ‘Banks are not purely high-end work. If it’s a high-end mandate, everyone will look at alternative fee arrangements. If it’s low margin, why would firms be bothered?’

However, one relationship partner with a top-25 UK firm says, while a few firms have the luxury of attracting masses of work from major clients without bowing to panel requirements, most have to conform and put the work in. ‘Kirkland & Ellis added $500m to its revenue last year. That didn’t happen by going onto panels and having masses of relationship accounts. We’re not in that position. We have to work for every piece of work we get and we’re happy about that – we get it. It’s challenging but it’s worth it.’