You wouldn’t mistake a lawyer for a designer. One is usually armed with a pen and a rulebook, the other with a Mac and a black turtleneck. Right? Wrong.

Until recent years, design thinking had not infiltrated legal services. But now, that has started to change.

A key player in marrying law with design has been Margaret Hagan, director of Stanford’s Legal Design Lab and a lecturer at the Stanford Institute of Design (known as the d.school). While a fellow at the d.school in 2013-14, she began experimenting with how design could enhance legal services, going on to become a key figure in developing programmes and courses for in-house and private practice professionals.

But she is not alone – others, like Josh Kubicki, chief strategy officer at Chicago-headquartered law firm Seyfarth Shaw, have also practised extensively in the field. Kubicki describes feeling ‘very alone’ at first. But now, he says, design thinking has become ‘quite a phenomenon’.

IDEO remains at the centre of developments. The company is structured around a culture that challenges the notion of creativity: ‘[Partner] Tom Kelley talks of this myth that innovation or an idea springs forth from the brain of the lone genius,’ says general counsel Rochael Soper Adranly. ‘That’s absolutely not the case. The innovations that we work on are the product of many minds and many iterations.’

This has meant a flat structure, where even new employees are free to pitch ideas and take advantage of a social contract that everyone freely interrupts everyone else. Legal is no exception to this concept of freeing the mind – so much so that 12 years ago, when the company was establishing an in-house legal function, it employed a design-thinking approach.

The concept

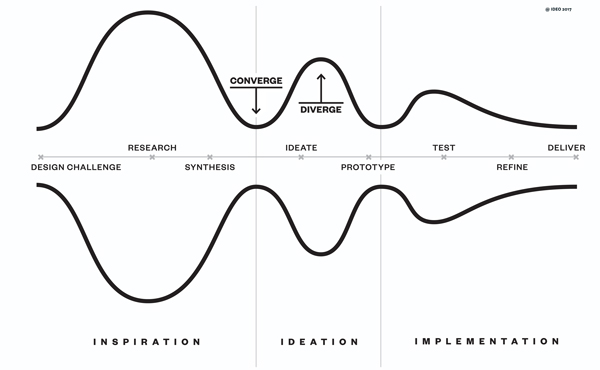

Design thinking puts the customer at the heart of the experience, framing them as a human being with problems, rather than a client facing challenges specific to their desired products. The designer must understand the subject’s needs within the broader business and market ecosystem, using rigorous questioning. Perspectives from outside the sector become important. All practitioners apply an investigatory, but above all else empathetic, approach. Then, rather than leaping to a solution, the design team brainstorms a range of concepts, testing until the concept is refined enough to be termed a solution.

Design thinking takes an expansive view of problems, teasing out the implied as well as the overt, applying inventive thinking to gradually solve issues the client might not have known they had. In other words, it is the opposite of the standard legal process and its carefully defined, precedent- and deadline-driven approach.

IDEO starts with an ‘immersion phase’, which goes beyond a fact-gathering session. This is termed as a ‘deep dive’ by a multidisciplinary team, into the user’s world, to uncover their acknowledged and unacknowledged needs.

The next stage is ‘synthesis’ – a search for patterns, and what IDEO calls ‘opportunity areas’, which form the basis for a brainstorm session. ‘It’s important not to rush this stage,’ says Adranly.

Slowing things down is key, especially during the prototyping phase, which involves breaking down what the team has learnt and testing it repeatedly. ‘That can happen one time, three times, ten times – whatever it takes. And then refining that out for implementation,’ she notes.

Not your typical GC

Adranly’s role as GC departs from the typical job description because she is also ‘legal design lead’ at the company, meaning she co-heads the legal design and innovation practice. This is a separate team at IDEO that uses design thinking methodology to train other in-house legal teams and law firms to innovate within their organisations. If the in-house team is not invited into business conversations at an early stage, it is too easy to veto ideas, and this is why Adranly and her legal design team work to bring legal and business teams into partnership.

She recalls: ‘One time a client had a question and I wondered why they were asking us that. As I dug further, they said: “We were afraid to ask our own legal team.”’

‘Through a series of conversations, we created a legal innovation workshop with their legal team and their product team to brainstorm through a lot of the issues. It was fantastic. The client’s legal team were phenomenal. They were great contributors.’

A typical IDEO project team for a legal design and innovation project will include a lawyer or lawyer-turned-designer along with designers from a variety of backgrounds – such as media, entertainment or even education – to bring fresh perspectives.

Does Adranly’s role make her a lawyer or a designer? Both, in her opinion. Her CV has swung from lawyer to artist, to representing artists, and back to law, giving her a fairly unique set of soft skills. In the same way, IDEO needs legal hires to have the ability to be part of problem-solving and collaboration throughout the organisation.

A Mac or a PC?

Andrew Baker is vice president and global head of services at LexPredict in Chicago, a consultancy that advises law firms and in-house departments on improving the way legal services are consumed, delivered and managed. Design thinking is an important component of LexPredict’s toolkit, but Baker admits that getting a project off the ground can involve fighting on two fronts. ‘You have to understand that you’re trying to improve two things simultaneously: one, the business objective and two, shaping and sculpting the mindset and openness of the people who are a part of that project early on.’

Blue-sky thinking can be anathema to sceptical lawyers. ‘Lawyers are fundamentally wed to precedent,’ says Baker, himself a law school graduate. ‘But in many cases you have to put precedent aside if you’re going into a project where design thinking techniques are used, and try to think completely anew.’

Adranly agrees that putting the client at the heart of the process can be a struggle if you think you are already an expert on their needs. ‘What causes some of the tensions with lawyers is that we think we’re so smart, we think we know what the client wants without having gotten super-curious about that.’

The expert can be the enemy of discovery, and also of the prototyping phase of design thinking, because lawyers are trained to get to solutions quickly. But an important component of design thinking is to embrace the prospect of failure to reach ultimate success. ‘Failure’, however, is not in the lawyer’s lexicon. To succeed at design thinking, they have to accept they do not know all the answers, just as designers have to accept that great ideas are not usually the product of one inspired mind.

This means spending time with others, both clients and service providers. From personal experience, Adranly acknowledges the difficulty of this, especially between in-house counsel and law firms, when corporate legal teams often have little time to spend giving outside teams a detailed picture of life in-house.

Baker points to a fallacy among firms that their profitability is a result of good client understanding. ‘Many firms think they are very client-centric. If you evaluate the number of firms that have meaningful programmes where the firm is reaching out in a systematic way to gain deep client insight and then pairing that insight with targeted investment, that’s fairly rare. There’s a disconnect between the organisation they believe they are and how they really operate,’ he says.

The trick is to become a problem-finder and develop a nose for what clients are implicitly signalling, rather than raising explicitly. ‘You have to have the right kind of facilitation, to turn over a stone that will lead you to something you wouldn’t otherwise have found,’ Baker argues.

Baker believes corporate legal departments are generally more open to new modes of thinking when it comes to overhauling service delivery. He has noticed design thinking concepts taking root in other business functions often creeping into the in-house legal team.

This describes the path to design thinking taken by Alex Gavis, deputy GC at Fidelity Investments. He became acquainted with the concept through business clients – Fidelity is unusual in having an entire group devoted to design thinking within its corporate innovation centre, Fidelity Labs. Gavis used this exposure as a springboard to broader involvement in the design thinking community, and along with Hagan, taught a pop-up class at the Stanford d.school designed to help aspiring lawyers and business professionals simplify their oral and written communications. After a successful run on the West Coast, he ran a similar course at Suffolk University Law School in Boston.

By using a design thinking approach, companies like Fidelity, that rely heavily on contracts, can spend time with both customers and business people to get a sense of what aspects of contractual language are confusing, and what goals that language is intended to achieve. This can result in clearer wording.

For Gavis, design thinking is about ‘falling in love with the client’s problem’. It allows lawyers to spend time empathising and interviewing, which can lead to more creative solutions. In his own in-house team, he has worked to broaden perspectives by bringing together lawyers from different disciplines to work on issues and train others in the group.

Baker has found that in-house legal teams are more likely than law firms to understand when they need to evolve strategically, due in large part to the legal operations movement. Kubicki agrees, adding that legal operations professionals are often the owners of change management, which is where he believes the real value of design thinking lies for in-house teams. ‘The power of design is to say: “You do have a problem, but it’s part of an ecosystem.” They start to recognise it’s a case of: “We can change this, but we might not be able to change that without addressing some other human needs of the value chain outside of legal,”’ Kubicki says.

Considering a legal problem in tandem with the needs of other groups can provide a collaborative solution that bears fruit across the whole business. It might also gain the sort of trust that transforms the persona of the in-house legal department from operational to strategic, according to Baker.

At IDEO, Adranly believes design thinking is going to pick up adherents: ‘The conversation used to be: “What’s this design thinking thing?” It evolved to, “We see the value, we just don’t know how to do it yet”, and now it’s: “We’ve been experimenting with design thinking but we need to accelerate and we can’t do it on our own.”’

Whether increased receptivity will lead to widespread adoption remains to be seen, but both branches of the legal profession stand to gain from any tool that helps them to stand in their clients’ shoes.

And across the world of legal services, riddled with ambiguity and disconnects, and increasingly looking to technology to solve its problems, work in this area might serve as a timely reminder to put the human at the centre – and leave it not to accident, but design.

catherine.wycherley@legalease.co.uk

Design thinking in private practice – Josh Kubicki, chief strategy officer, Seyfarth Shaw

‘Many firms were sending work from a practice area overseas or using augmented legal services contracts, but at Seyfarth Shaw, we didn’t want to do that for strategic reasons. The design challenge was: how do we design a new service model that can be nurtured within the current business model while extending value to the client?

We used a number of design approaches – one of which involved thinking about the client journey. We learned what is important to a certain type of client is not necessarily cost, and there were a number of unmet needs going undetected both by law firms and clients themselves.

We created “client playbooks”, which describe the client journey. Each of our clients has a different culture and touchpoints. We map those relationships and find the client’s perspective around the most effective methods of communicating with them. For example, how should the work be packaged? Is speed the most important factor? Perhaps it’s risk mitigation or triage?

We had these discussions with the client and then designed a team around that journey. We used a mix of technology and a new “talent track” of lawyers that removes the usual administration burdens that an associate or partner would be burdened with.

In the end, we created a service that’s providing cost, functional and technical value for the client that is materially different from a typical law firm model, while keeping it within the firm.’