On 18 September 2014, Scotland voted ‘no’ to the question ‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’. That has not meant an end to constitutional discussions and wranglings, however, with attention turning immediately to the further devolution of powers to the Scottish parliament.

The Scottish parliament will in any event be receiving new powers, with the Scotland Act 2012 having legislated to devolve taxes on landfill and property transactions, and an element of income tax. The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) and a new Scottish Landfill Tax will be introduced in April, with the Scottish Rate of Income Tax (SRIT) to follow in April 2016. The SRIT will see the main UK rates of tax (on non-savings income) reduced by 10p for ‘Scottish taxpayers’, with their rates then supplemented by the SRIT as fixed by the Scottish parliament.

For example, if the SRIT was set at 10%, there would be no difference between income tax rates in Scotland from the rest of the UK. However, if the main UK rates remained 20%, 40% and 45%, and the Scottish rate was 12%, the various Scottish rates would become 22%, 42% and 47%. This single rate would apply across the tax bands, so rates cannot be varied independently.

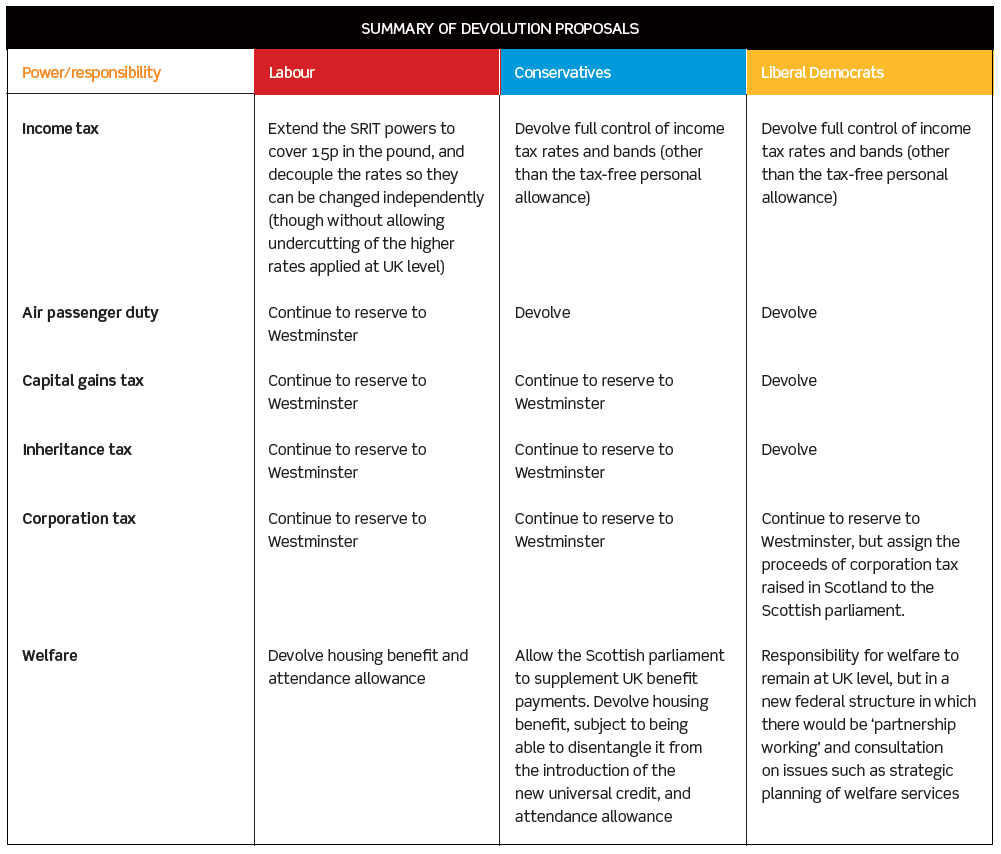

However, the principal pro-union parties took the view during the referendum campaign that these changes were insufficient to meet a perceived desire among voters for greater devolution. They therefore produced proposals in the spring for devolving additional powers in the event of a ‘no’ vote. These proposals focused chiefly on tax and welfare powers, and each party’s principal suggestions in those areas are briefly summarised (in the accompanying table (to the extent it is possible to summarise several hundred pages worth of proposals!)).

Then, over the final few weeks of the referendum campaign, the pro-union parties produced significantly more information on the process for delivering on those proposals. Former Prime Minister Gordon Brown set out a timetable for agreeing more powers, including:

- publication of a ‘command paper’ setting out agreed proposals by the end of October;

- a government white paper by the end of November (after a period of consultation); and

- draft legislation in January.

David Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg then published their now-famous ‘vow’ committing to that timetable in theDaily Record the week before the vote, and on 22 September a motion to that effect was placed before Parliament.

Barely an hour after the referendum result was confirmed, the prime minister announced that Lord Smith of Kelvin would be tasked with forming a consensus within that timetable on what powers should be delivered. The ‘Smith Commission’ has since been established, and each of Scotland’s main parties (including the SNP and Greens) has appointed two representatives. The Commission is also inviting civic society to make submissions on what further powers should be devolved to the Scottish parliament, though the timetable is extremely ambitious (particularly for considering potentially major constitutional changes), and it remains to be seen whether institutions and businesses will have enough time to make meaningful contributions.

Lord Smith has conceded that it will not be easy to reach agreement within the required timetable. As the table shows, there were areas of overlap among the unionist parties’ tax and welfare proposals but no consensus, with the Lib Dems proposing to go furthest and Labour being the most cautious. In addition to those issues, the Commission will also need to consider whether any other areas currently reserved to Westminster (per Schedule 5 to the Scotland Act 1998) should be devolved. For example, Labour has proposed giving the Scottish parliament control over its own electoral procedures, the administration of employment tribunals, and the enforcement of health and safety and equalities legislation.

There have also been suggestions for reforms that do not require any changes to the devolution settlement. For example, although the civil service will remain a reserved matter, the Conservatives have proposed requiring senior Scottish civil servants to spend time in UK government departments as part of their career progression. They have also proposed reforming the Scottish parliament’s internal procedures to strengthen opposition representation on its committees, and so improve legislative scrutiny, though the parliament has control over its own procedures. The pro-union parties are all agreed that local government should have greater autonomy, reversing the centralisation trend, but the Scottish parliament already has full control over Scottish local government. Such issues may therefore fall outside the Smith Commission’s scope, as the parties are unlikely to propose taking away or restricting any of the Scottish parliament’s existing powers.

Lord Smith’s task is further complicated by the fact that, now independence is off the table, the SNP and Greens are also contributing to the process. At the time of writing the SNP have not produced any detailed proposals for what powers they want to be devolved, but they have seized on a statement made by Gordon Brown in the run-up to the referendum that a ‘no’ vote would result in something close to ‘home rule’, and accompanying media coverage using the phrase ‘devo-max’ (despite the technical meaning of that being full devolution of everything other than defence and foreign affairs, which is a very unlikely scenario). The pro-union parties themselves said at the time that they were not proposing any additional powers beyond those they had already published, but the SNP are nevertheless arguing hard for a more extensive settlement that would see full devolution of taxation and welfare powers. While they are in the slightly odd position of treating a vote they did not win as a mandate to deliver powers they did not propose, there can be no doubt that they will seek to gain political leverage from any perceived failure by the other parties to live up to their pre-referendum commitments.

One area in which there seems to be a developing consensus is the notion that the Scottish parliament should be ‘permanently entrenched’, meaning that it should no longer be legally possible for the UK Parliament to dissolve it. This appeared in the Labour and Lib Dem proposals for further devolution, and has also been adopted by the SNP. However, the inability of one parliament to bind future parliaments is perhaps the fundamental principle of the (unwritten) UK constitution – in IT terms, it is not a bug but a feature.

Legislation abolishing the Scottish parliament is in political terms so unlikely as to be practically impossible (unless of course there is a significant change of heart in Scotland about the desirability of devolution), but the premise of the proposal is that those political constraints are insufficient. That does not mean it is possible to add legal constraints, however, as any Act that purported to prohibit Westminster from dissolving the Scottish parliament could itself be repealed (if not simply ignored) by a future parliament. There is therefore no legislation Westminster could pass that would prevent future parliaments from ‘reversing’ legislation purporting to make the Scottish parliament ‘indissoluble’, at least not without causing a constitutional revolution, and perhaps even a constitutional crisis. Tackling this issue would require the Smith Commission to go far beyond the question of more powers for Holyrood, into fundamental and even existential questions about the constitution of the UK as a whole. It may therefore find its way into the ‘too difficult’ pile.

Given the complexity of the issues and the competing political interests involved in the process, and in particular the short timetable, the outcome of the Smith Commission may simply be draft legislation that reflects whatever consensus can be reached in the time available, with the parties committing to enact the draft legislation in their manifestos for May’s UK general election.

It is not clear, however, whether the parties will be happy to treat Lord Smith’s process as conclusive. There will surely be some issues on which consensus will not be reached, and it would of course be open to each party to include their own proposals on those issues in their general election manifestoes. The winning party could then supplement the draft legislation after the general election to reflect those commitments. In particular, the Conservatives and Lib Dems may be unlikely to want to forego the opportunity of highlighting to Scottish voters where their proposals go further than Labour’s, and one can certainly expect the SNP and Greens to want to offer Scottish voters more powers than Lord Smith’s process is likely to produce. Furthermore, as with the Scotland Act 2012, the Scottish parliament’s consent will be sought on any new legislation, which could result in changes to the Smith ‘package’.

There will certainly not be enough time to actually introduce and enact legislation before the end of March, when Parliament will be dissolved for the general election, as any Bill would be immediately ‘guillotined’ at that point and have to start again from scratch in the new parliament. There are, of course, other means by which further powers could be delivered: the Scotland Act 1998 allows for the boundaries of devolution to be revised by way of a ‘section 30 order’, while the Scotland Act 2012 also introduced the power to devolve (further) taxes by order in council. However, all the indications are that a new Scotland Bill would be introduced immediately after the election.

That seems to be the case notwithstanding the prime minister’s desire to resolve issues over how to deal with ‘non-Scottish’ Westminster legislation ‘in tandem with’ further devolution for Scotland. There does not seem to be any chance of consensus among the UK parties on that issue, but if the Conservatives win the general election they will of course be in a position to reform how English legislation is dealt with at the same time as delivering Scottish devolution. If they do not win, their views on ‘linking’ the two issues will not matter as responsibility for delivering more devolution will fall to the winning party (or coalition). There is therefore no reason in principle why further devolution to Scotland need be conditional on the parties also reaching consensus on ‘the English question’.

Significant questions nevertheless remain. It is clear that September’s ‘no’ vote is not the end of the debate on Scotland’s constitutional future, but (and with apologies to Churchill) it remains to be seen whether Lord Smith’s process is the beginning of the end, or just the end of the beginning.